Depth of discharge (DOD) is how deeply you cycle a battery, and this guide shows how that choice controls usable capacity, lifespan, and the return on your solar or off-grid storage investment.

Picture this: the lights are on in your cabin, the fridge is humming, the well pump kicks in, and your "10 kWh" battery bank hits empty hours before sunrise. You sized it by nameplate, not by how deeply you could safely drain it, and now you are burning gas in a generator you thought you had retired. When you design around the right depth of discharge and cycle life, the same hardware can deliver dramatically more energy before it ever needs replacement.

The Simple Meaning Behind Depth of Discharge

At its core, depth of discharge, usually shortened to DOD, is the share of a battery's total capacity that you have used since it was last full. If you start at full and use half the stored energy, that cycle has a 50 percent DOD. Use eight kilowatt-hours out of a ten kilowatt-hour pack and you are at 80 percent DOD. In technical terms, DOD is the mirror image of state of charge, so the two always add up to 100 percent, a relationship described in battery engineering references on depth of discharge and reiterated in solar storage primers such as Battery Storage 101.

You will see DOD in two slightly different ways. Sometimes it describes the instantaneous amount you have already taken out in a single cycle, and sometimes it describes the normal window you plan to use every day, such as "we operate this pack between 20 and 90 percent state of charge, so our normal DOD is 70 percent." Both uses follow the same math but serve different purposes: the first tells you when to stop discharging right now, and the second tells you how hard you are working that battery over its life, a distinction highlighted in engineering overviews from PEM Motion.

For real projects, DOD matters because what you buy is nominal capacity, but what you actually live on is usable capacity. If a lithium home battery is rated at 12 kWh and has a recommended DOD of 80 percent, you only plan on using 9.6 kWh in a normal cycle; the rest is intentional headroom to protect the cells. Consumer-facing explainers, including GivEnergy's plain-language guide to depth of discharge, emphasize that usable energy is simply nominal capacity multiplied by DOD.

Manufacturers sometimes go further and hide extra capacity inside the pack so the marketing label stays attractive while the cells themselves never see the advertised extremes. A home unit labeled as 10 kWh might physically hold around 12 kWh, and if you are told it can run all the way from "full" to "empty," the internal DOD is really closer to 83 percent, a tactic discussed in home-storage comparisons such as Understanding Depth of Discharge. That trick protects the battery, but it also means you cannot compare value across products without understanding DOD.

How DOD Controls Lifespan and Lifetime Kilowatt-Hours

Once you understand that DOD sets your usable energy per cycle, the next step is realizing it also sets how many cycles you get. Across chemistries, deeper average DOD means more chemical and mechanical stress per cycle and fewer total cycles before the battery fades to the end of its useful life. Technical summaries from PEM Motion and industry explainers like What You Need to Know About Depth of Discharge both highlight this: operating around 20 to 30 percent DOD can roughly double the cycle count versus consistently pushing toward 80 percent or more.

For lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) home batteries, one data set shows about 12,000 cycles when you only use around 20 percent of capacity each time, about 6,000 cycles at 50 percent DOD, roughly 3,500 cycles at 80 percent, and closer to 2,000 cycles at a full 100 percent DOD. That steep drop as you run deeper illustrates the life penalty for squeezing out every last amp-hour, as summarized in shallow-versus-deep guidance for LFP home storage on Anern’s discharge comparison.

Electric-vehicle tests back up the same pattern. Analysis of EV cycling experiments compiled by Recurrent Auto shows that reducing DOD from nearly full swings to more moderate ranges can multiply expected life by several times, with cells operated between mid-range charge limits losing significantly less capacity than those repeatedly swung from almost full to almost empty, a conclusion drawn in their review of one simple trick to extend EV battery life.

Shallow vs. Deep: Lifetime Energy and ROI in Plain Numbers

The ROI impact shows up when you look at total energy delivered over the battery's life rather than just how many years it sits on the wall. Capture Energy illustrates this with a simple comparison: imagine a 10 kWh battery that is run at 100 percent DOD and rated for 1,000 cycles versus another 10 kWh battery limited to 50 percent DOD but rated for 3,000 cycles. In the first case you get 10 kWh per cycle times 1,000 cycles, or 10,000 kWh over its life; in the second you get 5 kWh per cycle times 3,000 cycles, or 15,000 kWh, even though you are using only half the pack each time, an example drawn from their discussion of depth of discharge.

That means, if both batteries cost the same, the one that lives at 50 percent DOD is effectively delivering about 50 percent more energy per dollar. For an LFP pack following the cycle-life curve mentioned earlier, the trade-off is still substantial: at 20 percent DOD and around 12,000 cycles, a 10 kWh pack delivers roughly 24,000 kWh over its life, while at 100 percent DOD and about 2,000 cycles it delivers about 20,000 kWh. You might use more energy per night at 100 percent DOD, but you burn through the cycle count so quickly that lifetime throughput falls behind.

Real systems do not run at a single, fixed DOD forever, but the direction is clear. As references from PEM Motion and Recurrent Auto both emphasize, moderate DODs significantly cut degradation, which translates directly into more cycles and more total kilowatt-hours for every dollar you lock into storage.

Chemistry and DOD: Why Lithium Retrofits Change the Game

When you retrofit from older lead-acid banks to modern lithium, the biggest change is not just higher nameplate capacity; it is the much deeper safe DOD. Traditional lead-acid batteries, whether flooded or sealed, typically should only be discharged to about 50 percent if you want decent life, so a 10 kWh lead-acid bank has only about 5 kWh of practical daily energy, a rule of thumb echoed in home storage introductions like Battery Storage 101 and residential guides Solar Optimum.

By contrast, mainstream lithium-ion home batteries are commonly rated for around 80 to 95 percent DOD without taking a big hit to cycle life. Sources focused on residential systems note that many premium lithium models allow up to 100 percent DOD under their warranty terms, particularly when using lithium-iron-phosphate chemistry, which is more robust to deep cycling than older nickel-manganese-cobalt chemistries, as described in home-storage comparisons from Solar Optimum and detailed DOD discussions from Capture Energy.

EcoFlow provides a concrete example of what that means in day-to-day use. In their portable and stationary storage explainer, a 3.6 kWh lead-acid battery with a recommended 50 percent DOD yields only about 1.8 kWh of usable energy per cycle, while the same 3.6 kWh in LiFePO4 form, operated around 80 percent DOD, yields roughly 2.9 kWh. That is about 60 percent more usable energy per cycle from the same nameplate capacity, purely because the chemistry allows deeper safe discharge, as outlined in their guide to depth of discharge for batteries.

The newest generation of LFP-based home batteries push this even further. For example, residential systems such as Tesla's LFP-based Powerwall 3 are marketed with 100 percent usable DOD, leveraging the chemistry's ability to tolerate deep discharge with long cycle life, and solar installers describe this as a key reason these batteries are suited for daily cycling and off-grid duty, a theme in comparisons of modern residential batteries from Solar Optimum and technical DOD analyses from Capture Energy.

Typical Recommended DOD by Chemistry

The result is that different chemistries deliver very different usable energy from the same nominal capacity. Summarizing guidance across home-storage references gives a clear pattern.

Chemistry |

Typical recommended DOD range |

Practical notes |

Flooded / AGM lead-acid |

About 30-50% |

Best life when kept shallow; going much deeper repeatedly shortens life quickly. |

Lithium-ion (NMC, etc.) |

About 80-90% |

Offers much more usable daily energy than lead-acid from the same kWh rating. |

Lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) |

About 90-100% |

Can safely support very deep cycles with long life, especially when managed by a BMS. |

These ranges align with explanations in sources like Battery Storage 101 for lead-acid versus lithium, EcoFlow's comparison of lead-acid and LiFePO4 in their DoD overview, and LFP-specific discharge and cycle-life curves for home batteries in Anern's shallow vs deep discharge guide.

From an ROI standpoint, this table explains why lithium retrofits almost always shrink the physical battery bank while boosting usable energy and lifetime throughput.

You are paying to move from a world where half your nameplate is off-limits to a world where you can confidently use most of what you bought.

Designing DOD for Maximum ROI in Your Off-Grid or Retrofit Project

Getting the right DOD strategy is not about memorizing someone else's "magic number." It is about matching system size, chemistry, and controls to how you actually live.

First Question: How Many Kilowatt-Hours Do You Truly Use?

Start by estimating your real daily energy use. If your cabin consumes around 10 kWh overnight, and you are installing an LFP battery rated for 80 percent DOD, you need at least 12.5 kWh of nominal capacity to cover that comfortably, because 12.5 multiplied by 0.8 yields your 10 kWh target. This simple usable-capacity calculation is the same one used in consumer explanations of DOD in both GivEnergy's "Explain like I'm 5" article and solar-battery sizing guides like "Nominal vs usable capacity" that distinguish rated from usable storage.

If, instead, you choose a much smaller pack and routinely pull 90 to 100 percent of its rated capacity each night, you may survive the first few seasons, but you will hammer the cycle life and be buying a replacement years earlier than planned. That is exactly the pattern seen when shallow and deep discharge curves for LFP storage are compared side by side in Anern's shallow vs deep discharge analysis.

Second Question: Is Your Priority Independence Today or Lowest Long-Term Cost?

If your main goal is resilience—staying powered through long outages or cloudy streaks—then pushing to higher average DOD on a robust chemistry like LFP can be a smart, deliberate trade. You might design a system that normally runs around 70 to 80 percent DOD, accepting somewhat faster wear in exchange for fewer compromises on the loads you run. Guides aimed at homeowners who prioritize self-consumption and backup, such as the overview in Battery Storage 101, highlight that modern lithium systems can tolerate such deep daily cycling when properly sized and managed.

If, on the other hand, you care most about wringing the lowest possible cost per kilowatt-hour out of your batteries over one or two decades, the better play is to slightly oversize capacity and intentionally keep daily DOD shallower. Technical write-ups on DOD from PEM Motion and real-world discharge data rounded up in Recurrent's EV battery life review both show that living in the mid-range of a pack's charge window can significantly extend life compared with constantly swinging from near full to near empty.

On the lead-acid side, conservative DOD is almost mandatory if you want respectable life. Off-grid design notes from manufacturers and distributors, echoed in summary form in What You Need to Know About Depth of Discharge, recommend sizing banks so routine operation does not exceed roughly 50 percent DOD. If usage data shows your system regularly diving below this point, the standard corrective move is adding capacity rather than accepting chronic deep discharge and short battery life.

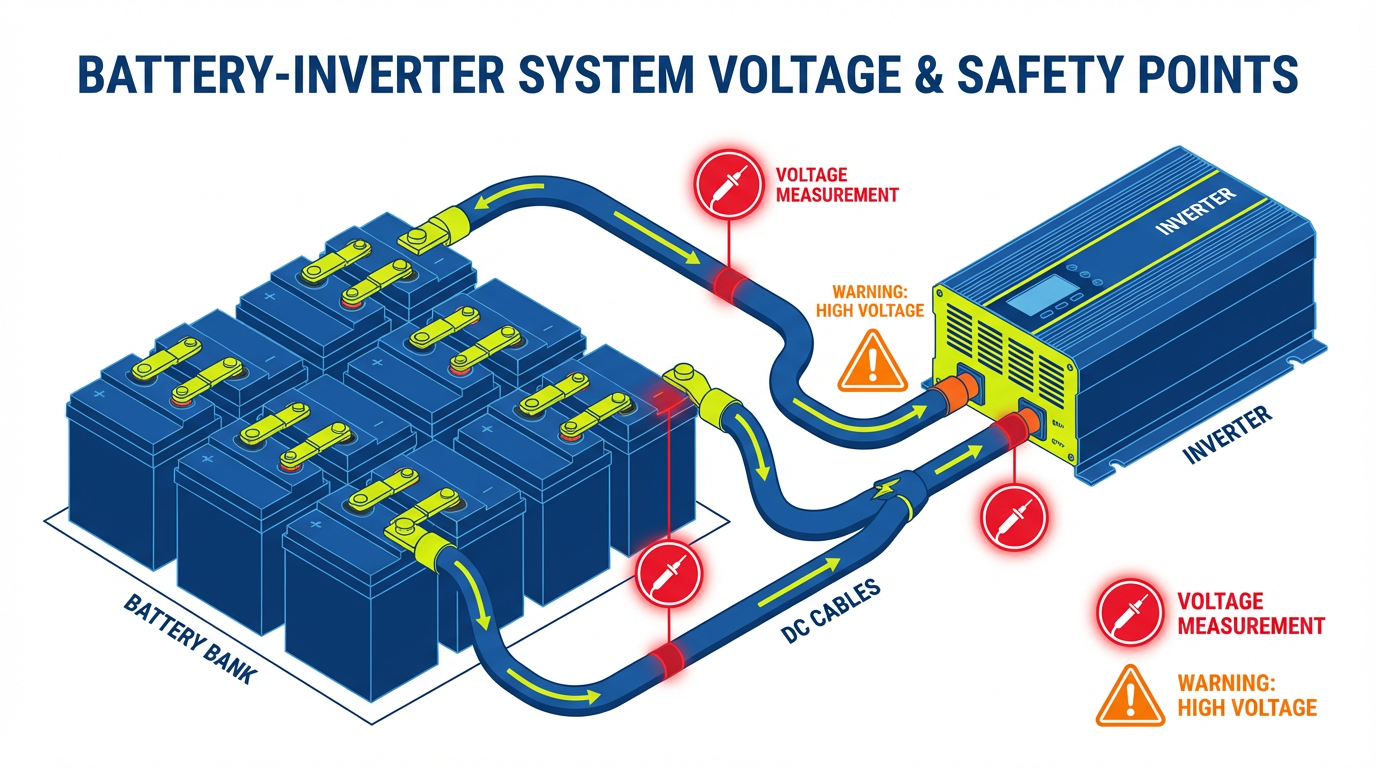

Third Question: How Will Your BMS and Controls Enforce That DOD?

Whatever DOD target you choose, it only matters if your controls actually stick to it. Modern lithium packs ship with integrated battery management systems that constantly estimate state of charge and cut off charging or discharging at manufacturer-defined limits. Engineering glossaries like PEM Motion's DOD entry and system-design guides from storage vendors such as Hinen emphasize that these BMS algorithms track voltage, current, temperature, and history to keep DOD within safe bounds.

For home storage, you often have additional control at the inverter or app level. You might set a minimum state of charge of 20 percent so the system never intentionally discharges below that, which caps daily DOD at 80 percent. Home-storage guides that compare shallow and deep operation, including Anern's discharge strategy article, recommend exactly this approach: let the battery deliver deep discharges when needed during outages, but default to milder DOD during everyday operation.

The same logic shows up in other domains. Smartphone makers now offer "optimized charging" modes that hover in a mid-range rather than sitting at 100 percent all night, and EV makers quietly hide some buffer at the top and bottom of their packs, so the "0 to 100 percent" you see on the dash is actually a narrower internal DOD window, a buffer strategy explored empirically in Recurrent's EV DOD analysis. Your home system can and should be configured with the same philosophy.

FAQ: Quick Answers on DOD and ROI

Is It Okay to Run an LFP Home Battery to Zero Every Night?

An occasional deep discharge on a quality LFP pack is fine and one reason this chemistry is favored for off-grid homes, but making 90 to 100 percent DOD your daily habit will still cut cycle life. Cycle-life curves for LFP at different DOD levels, such as those summarized in Anern's LiFePO4 discharge guide, show far higher cycle counts at 50 to 80 percent DOD than at 100 percent. If you want maximum ROI, aim to live in that moderate band most of the time and reserve true zero for emergencies.

How Low Should I Let a Lead-Acid Bank Go in an Off-Grid System?

For deep-cycle lead-acid, practical system-design guidance consistently points to a target around 50 percent DOD for regular use, which means you recharge when the bank is roughly half empty. Explainers written for home storage, including Battery Storage 101 and EcoFlow's DOD overview, caution that repeatedly going much deeper than this will rapidly shorten life. If your logs show frequent dives below that point, adding capacity or shedding loads is usually cheaper than burning through batteries.

Can I Change My DOD Strategy Later Without Replacing Hardware?

In most lithium systems, yes. As long as your hardware supports it, you can adjust minimum and maximum state-of-charge settings in the inverter or app so the BMS keeps DOD within a new window. Technical discussions of DOD management in grid-connected systems, such as the overview from PEM Motion, describe dynamic DOD control as a core tool for balancing energy throughput against degradation. Practically, that means you can start with a conservative DOD while you learn your usage, then widen or tighten the window as your priorities or tariffs change.

A battery upgrade is not just about swapping chemistry or adding kWh; it is about choosing how hard you work that storage every single day. When you treat depth of discharge as a design lever instead of a footnote, you size the bank correctly, pick the right chemistry, and program your controls so every amp-hour you pull moves you closer to the payback you planned.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.