Cycle life is the number of full charge-discharge equivalents a battery can deliver before its usable capacity falls to about 80% of its original value, and several partial uses add up to one full cycle.

Picture this: you wake up off-grid after a cloudy stretch, your inverter is still running, and you are wondering whether last night’s “light use” quietly burned one more precious cycle from that expensive lithium bank. That question shows up in almost every retrofit or cabin upgrade, and the owners who get it right routinely stretch their battery life from a few years to well over a decade simply by changing how deeply they cycle each day. This guide breaks down what a cycle really is, how half-power days are counted, and how to turn that knowledge into extra years of life from your lithium or lead-acid bank.

The Short Answer: Does Half Power Count as a Cycle?

A battery cycle is about total energy moved, not how many times you plug in the charger or how many sunsets you run through.

Most technical sources define cycle life as the number of complete charge-discharge cycles a battery can perform before its capacity falls to a set threshold, commonly around 80% of the original capacity, which is when the drop in runtime becomes obvious. Engineering references and energy-storage guides describe it this way, and manufacturers from lithium specialists to grid-storage suppliers follow the same convention.

Crucially, a “cycle” is a full equivalent, not a single day. Industry explanations from sources such as ChinaGode and NCBell (NBCell Energy) make it clear that several partial discharges that add up to 100% of the rated capacity count as one cycle. If you repeatedly use about half the battery and then charge it back, each of those days is roughly half a cycle. After two such days, you have consumed about one full cycle. Four days at around 25% use per night is also about one full cycle.

A simple example makes this concrete. Take a 10 kWh lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4) bank. If you use 5 kWh overnight (half the bank) and recharge to the same top level the next day, that is roughly 0.5 cycle. Do that two nights in a row, and you have put about one cycle on the pack. If you instead drain 8 kWh in one long stormy night and then recharge, that single night is about 0.8 cycle. Over time, your battery management system or external battery monitor aggregates all those partial in-and-out flows into full equivalent cycles.

What Cycle Life Really Measures

Cycle life is not just how many times you charged the battery. It is a standardized way to compare how long different batteries can work before they have aged to the point where they only hold a fraction of their original energy.

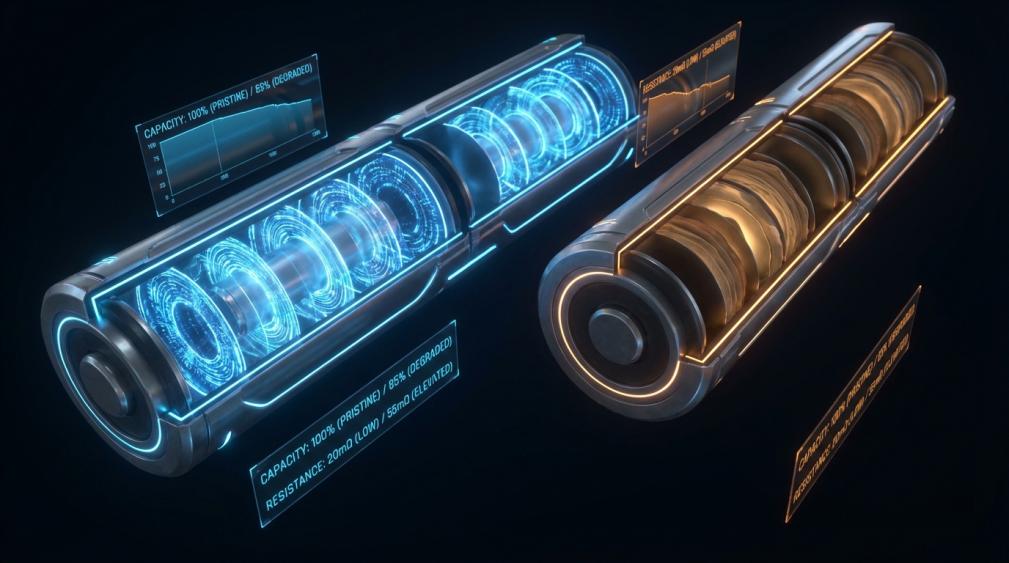

Technical definitions from organizations cited in sustainability literature and manufacturers like NBCell Energy and BioennoPower converge on the same core idea. A battery’s cycle life is the number of complete charge-discharge cycles it can undergo under defined conditions until its usable capacity falls to about 70–80% of its original value. Battery University and other engineering sources use that 80% mark as a practical end-of-life reference, because that is where people really start to notice that runtime and power output are down.

Those “defined conditions” matter. In formal tests, labs hold temperature around a comfortable room value, typically near 77°F, use a fixed charge and discharge rate, and keep voltage limits and depth of discharge consistent. ChinaGode’s overview of cycle-life testing notes that capacity is measured at the beginning, then rechecked periodically during cycling; once the current capacity divided by the original capacity drops below the 80% threshold, the cycle count at that moment is logged as the cycle life.

There is also a difference between cycle life and calendar life. Even when a battery sits mostly idle, chemical reactions slowly steal capacity. Energy-systems references emphasize that real-world battery longevity depends on both how many full equivalents you cycle and how many years the pack has simply existed, especially at high temperature or high state of charge. For an off-grid system, this means you are managing both how hard you cycle the bank and where it spends its time on the gauge.

Depth of Discharge: The Lever That Moves Cycle Life

The single biggest lever you control day to day is depth of discharge, the percentage of stored energy you pull out before recharging.

Depth of discharge, or DoD, is simply how much you use. If you have a 100 amp-hour battery and you take out 40 amp-hours before recharging, that is 40% DoD. The same idea holds for energy in kilowatt-hours: drawing 8 kWh from a 10 kWh bank is 80% DoD, which leaves 20% state of charge.

Multiple independent sources, including sustainable-energy glossaries, Dragonfly Energy’s testing on deep-cycle batteries, and analytical work cited by Recurrent Auto and Battery University, all point to the same relationship: deeper regular discharges shorten life, while shallower cycles stretch it dramatically.

One LiFePO4 data set summarized by Anern shows:

Regular DoD per cycle |

Approximate LiFePO4 cycle life (to about 80% capacity) |

100% (full discharge) |

around 3,000 cycles |

80% |

around 5,000 cycles |

50% |

around 8,000 cycles |

30% |

12,000 or more cycles |

This pattern lines up with the broader research that Recurrent Auto summarizes from several studies: a battery cycled at about 50% DoD can last roughly four times as many cycles as the same chemistry pushed routinely through full 0–100% depth. Battery University’s experiments likewise show significantly more cycles at 40–50% DoD than at 70–80% for common lithium-ion chemistries.

In practical terms, if you treat a 10 kWh LiFePO4 bank like a gas tank you run almost empty every night, you may see something like 3,000 to 5,000 full-equivalent cycles before it has sagged to about 80% of its original capacity.

With one full equivalent per day, that is roughly eight to thirteen years. If you instead size and operate the system so that you normally use only about half the bank daily, the same data suggest the pack could deliver in the neighborhood of 8,000 full equivalents. At one per day, that is over twenty years of cycling capacity on paper, even though calendar aging will usually set a practical ceiling before you reach the theoretical maximum.

This is the logic behind running lithium banks in a mid-range of state of charge. EV data from Geotab, AAA, and others show that lithium cells are most comfortable in the middle of their charge range, and EV-focused recommendations from groups like Chargie and independent EV blogs converge on keeping everyday use roughly between 20% and 80% whenever possible. Forum discussions built on Jeff Dahn’s laboratory results for lithium-ion even suggest a narrower window, often around 40–70%, for truly cycle-life-maximizing operation. Your solar or off-grid bank follows the same chemistry rules.

Chemistry Choices: Why LiFePO4 Wins for Off-Grid

Not every battery type responds the same way. Chemistry is the second major lever that determines how forgiving your system will be.

Lead-acid batteries, especially flooded deep-cycle designs, are far more sensitive to deep discharge and heat than lithium iron phosphate. Cycle-life summaries from NBCell Energy and BioennoPower show that typical automotive-style lead-acid units may provide only about 200–300 full cycles, with better deep-cycle versions in the neighborhood of 400–600 cycles and some premium types approaching 1,000 under gentle use. Dragonfly Energy and others point out that regularly taking a lead-acid bank down to 80% DoD can cut its life roughly in half compared with stopping at about 50%, and that staying in the 10–50% DoD band is much kinder.

Lithium chemistries vary as well. Standard consumer lithium-ion cells often deliver on the order of 300–500 full cycles in heavy use, rising toward 1,000 for quality packs. LiFePO4 cells, by contrast, are routinely rated around 3,000–5,000 full cycles and, in grid-storage or premium off-grid versions, can go far beyond 6,000 cycles when run at moderate DoD and sensible temperatures. Energy-storage manufacturers and independent analyses both highlight LiFePO4’s very low aging index: even after thousands of cycles, many LiFePO4 packs still hold around 80% of their original capacity, which is why they have become the default choice for serious off-grid and retrofit work.

A brief comparison makes the tradeoff clear:

Chemistry |

Typical full-cycle life to about 80% capacity |

Practical notes for off-grid |

Lead-acid deep-cycle |

roughly 400–600 (some premium near 1,000) |

Try not to discharge below about 50% routinely; avoid heat; needs more maintenance. |

Standard lithium-ion |

about 300–1,000 depending on design |

High energy density but more sensitive to voltage extremes and heat. |

LiFePO4 (LFP) |

commonly 3,000–5,000+, some storage cells 6,000+ |

Handles deeper DoD and heat better; ideal for daily cycling and long service life. |

For a retrofit, this means that spending more upfront on a LiFePO4 bank and then operating it at modest depth of discharge often produces the lowest cost per kilowatt-hour delivered over the life of the system, in line with lifecycle-cost analyses discussed in sustainable energy references.

How to Count Cycles in Your Own System

Most modern lithium packs and smart monitors already track cycles internally using coulomb counting, which tallies current in and out and compares it with rated capacity. Devices like the Victron BMV series and similar units use battery-specific parameters, such as the Peukert constant supplied by the manufacturer, to make this counting accurate.

You can estimate the same thing manually. Over any period, add up the approximate percentage of capacity you use before each recharge, then divide by 100. If across seven days you draw about 40%, 60%, 50%, 30%, 70%, 40%, and 60% of your usable capacity each day, that totals 350%. Dividing by 100 yields 3.5 full-equivalent cycles for the week. It does not matter whether those partial uses come from overnight cabin loads, running tools in the afternoon, or a fridge plus well pump in the evening; what matters is the sum of energy moved through the battery.

From this perspective, the original question has a clean answer. Using half the battery’s usable energy in a day counts as half a cycle, not one. When your cumulative withdrawals reach the equivalent of 100% of the rated capacity, you have logged one full cycle. The art of off-grid design is to decide how many of those full-equivalent cycles you expect the bank to see over its lifetime and to choose chemistry, capacity, and daily operating habits that keep those cycles as gentle as possible.

Operating Strategy: How Much of Your Bank Should You Use?

To turn all of this into practical design and daily habits, start from your load profile and work backward.

Guides on LiFePO4 system design, such as those summarized by Anern, recommend sizing off-grid banks so that average daily use lands around 50–60% DoD. For a home that consumes about 10 kWh per day from the battery at night and during cloudy hours, that suggests a bank in the 16–20 kWh range. In practice, many serious system designers go even larger, targeting closer to 30–50% daily DoD to take advantage of the dramatic increase in projected cycle life at shallower depths.

For systems used only occasionally, like a cabin visited on weekends or a backup bank that runs during utility outages, higher DoD is acceptable. Anern notes that home backup systems can tolerate 80–90% DoD because heavy cycling days are rare, and Dragonfly Energy’s testing on high-quality lithium batteries shows that some models are explicitly rated for 100% DoD without excessive damage, provided temperatures and charge rates are kept in check.

For lead-acid, the picture is less forgiving. Both Dragonfly’s data and traditional battery-care guidance advise avoiding discharges below about 50% whenever possible. Cycling to about 50% instead of 80% can roughly double cycle life, and staying in the 10–50% band can extend it by a factor of four or five, although that depth is often impractical unless you oversize the bank significantly. If you are retrofitting an existing lead-acid system and cannot change the batteries immediately, adjusting loads and charging to keep the bank around the upper half of its capacity and finishing full charge cycles (including absorption and equalization where appropriate) will make a meaningful difference.

On top of DoD, temperature and charge rate complete the picture. Studies and manufacturer data compiled by AAA, Dragonfly Energy, energy-sustainability references, and Geotab all agree that around 77°F is a sweet spot for lithium and lead-acid alike. Heat is the enemy: for lead-acid, every rise of about 15°F above 77°F can roughly halve cycle life, and lithium batteries also age faster at high temperature even if they continue to perform well in the short term. Fast charging and high current draw add extra heat and internal stress. That is why EV and battery-care articles across the spectrum recommend minimizing frequent fast charging, keeping packs away from prolonged high or low state of charge, and relying on built-in battery management systems to enforce safe voltage and current limits.

For a real-world off-grid setup, this translates into a few simple practices. Place the battery bank in a shaded, ventilated space rather than under a sun-baked metal roof. Let your inverter or charge controller ramp down charge current as the pack approaches full, rather than forcing maximum current to the very top. Set conservative low-voltage cutoffs so your inverter disconnects loads before the cells are driven into damagingly low state of charge. Use any charge-limit or storage modes available in your inverter or integrated battery to keep the pack in a comfortable mid-range when you leave the cabin for extended periods.

FAQ

If I only use about 50% of my LiFePO4 bank each day and recharge, is that considered gentle use?

Yes. Data aggregated by manufacturers and analyzed by sources like Anern, Recurrent Auto, and Battery University support the idea that daily cycling around 30–60% DoD is very favorable for LiFePO4. Compared with routinely going from nearly full to nearly empty, operating in that mid-range can multiply the number of full-equivalent cycles you get before the battery falls to about 80% of its original capacity.

Do I need to fully discharge my lithium bank occasionally to reset it?

No. The old memory effect advice applied to nickel-cadmium batteries, not to modern lithium-ion or LiFePO4. Contemporary guides on cycle life and depth of discharge, including those focused on solar and off-grid systems, explicitly call deep forced discharges harmful for lithium batteries. Light to moderate cycling with occasional deeper discharges when you truly need them is healthier than repeatedly running to empty.

Is it okay to charge to 100% sometimes?

Occasional full charges are fine and sometimes necessary, especially before a long stretch of bad weather. Technical discussions around EVs and energy storage, including Tesla-focused and broader EV guidance, emphasize that the real harm comes from living at the extremes: frequently charging to 100% and leaving the battery there for long periods, or letting it sit near empty. For off-grid systems, charging to full ahead of a storm and then letting the pack naturally drift back into a mid-range is a reasonable compromise.

A battery bank is not just a silent box of amps; it is a long-term asset whose lifespan depends on how you treat each invisible cycle. When you design around moderate depth of discharge, choose the right chemistry, control heat, and let your electronics enforce sane limits, you are not just protecting gear—you are buying yourself quieter nights, fewer emergency swaps, and more years of reliable off-grid power from every dollar invested in storage.

References

- https://www.blackridgeresearch.com/blog/top-tips-to-maximize-electric-vehicle-ev-battery-life-capacity-longevity-performance?srsltid=AfmBOooaN6da31HwUukmu4ot9fHDD6Ncw5X27v2f-BIbHvorUPYrgFJk

- https://www.chargie.com/resources/what-is-the-80-20-rule-of-ev-charging#:~:text=What%20is%20the%2080%2F20%20Rule%20in%20EV%20Charging,exceeding%20the%20range%20whenever%20possible.

- https://powersavingsolutions.co.uk/4-reasons-why-lithium-batteries-win-over-lead-acid-for-energy-storage/#:~:text=Lithium%2Dion%20batteries%20generally%20have,capacity%20during%20the%20cycle%20life.

- https://dragonflyenergy.com/battery-life-cycle/

- https://nbcellenergy.com/what-is-cycle-life-of-battery/

- https://www.recurrentauto.com/research/one-simple-trick

- https://mwg.aaa.com/via/car/how-extend-life-electric-vehicle-batteries

- https://www.anernstore.com/blogs/diy-solar-guides/cycle-life-depth-discharge?srsltid=AfmBOoqioogum7i3jgpboTq9JaS_ln2vXBZDQPujcHHKgHbOwbWQIJHb

- http://www.batteryuniversity.com/article/bu-808-how-to-prolong-lithium-based-batteries/

- https://www.bioennopower.com/blogs/news/understanding-battery-cycle-life-importance?srsltid=AfmBOort6ZHqZ5NxTmPw9zXe9rHRJBOq4CUFZfLjffwbLv0PnmX7WXns

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.