Batteries do not create electricity; they store the energy you put into them and return a bit less, like a bucket that always leaks a little between filling and pouring.

Picture an off-grid cabin that just added a sleek lithium battery bank, yet the lights still sag before dawn and the generator still fires up after a cloudy stretch. The problem is usually not the brand of battery; it is the hidden assumption that the battery generates power instead of simply storing what your solar array, wind turbine, or grid-tied service already produced. Once you start treating your battery bank as a finite bucket with known losses, you can size it properly, pair it with the right charging sources, and finally get predictable, dependable power instead of surprises.

Energy 101: Why No Battery Can Create Power from Nothing

Energy storage is simply capturing energy produced at one time so you can use it later. That is how major references on energy storage describe it and why technologies from hydro dams to lithium packs are called storage rather than sources. A battery belongs in the same family as pumped hydro or a flywheel: it is an accumulator that holds energy and then releases part of it later, never more.

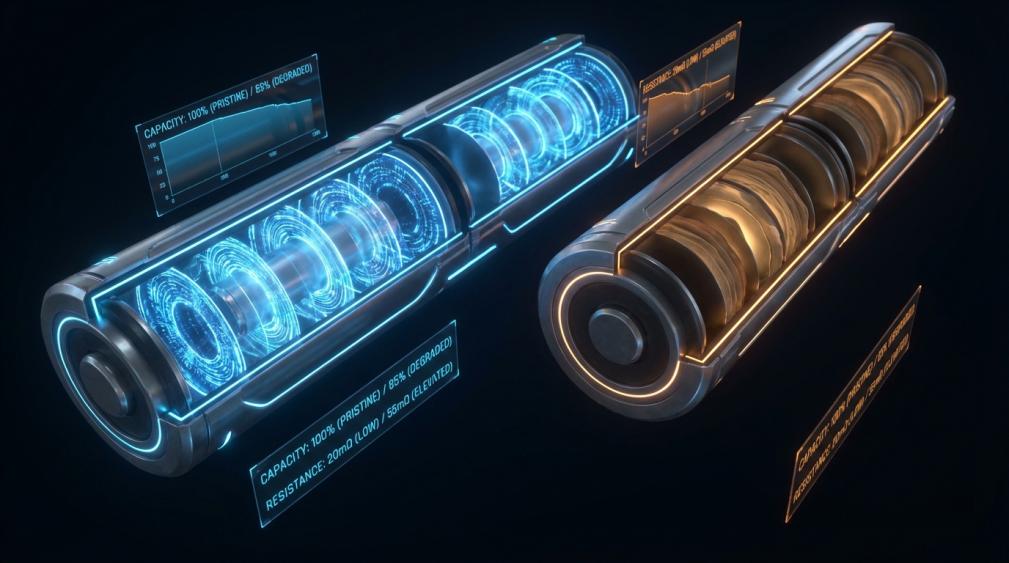

At the microscopic level, a battery stores energy in chemical form. Scientific explanations from sources such as Scientific American and the U.S. Department of Energy describe the same picture: two electrodes (anode and cathode) sit in an electrolyte, and the materials are chosen so that specific chemical reactions can release or accept electrons. During discharge, the anode undergoes an oxidation reaction that frees electrons, and the cathode undergoes a reduction reaction that consumes them. The electrolyte lets ions move inside the cell while blocking electrons, so electrons are forced to flow through your wiring and loads, doing useful work along the way.

In rechargeable cells, those reactions are reversible. When you charge, an external power source pushes electrons in the opposite direction and drives ions back to a higher-energy chemical arrangement. The Department of Energy describes this as moving energy into and out of chemical potential, much like lifting a weight and letting it fall later. The key point is that the energy comes from whatever is charging the battery: the grid, your photovoltaic (PV) array, a wind turbine, or a generator. The battery just gives you timing flexibility.

Every step in this process wastes a little energy as heat and as losses in wiring, electronics, and internal chemistry. That is why real storage systems are rated by round-trip efficiency. Bulk pumped-hydro systems, which act as giant water batteries, typically return around 70 to 80 percent of the electricity used to pump water uphill, sometimes a bit higher in optimized plants. Modern lithium-ion systems used in battery energy storage projects can return up to roughly 90 percent of what they take in according to utility and manufacturer data. In other words, you never get more out than you put in, and you always get a little less.

How Batteries Actually Store Energy: From Volts and Amp-Hours to Usable kWh

For practical design, three simple numbers describe a battery: voltage (V), capacity in ampere-hours (Ah), and stored energy in watt-hours (Wh). Industry guides explain the basic relationship as Wh = V x Ah. That formula is not marketing; it is your first sizing tool for off-grid and retrofit work.

Imagine a residential lithium system in the common 5 to 15 kilowatt-hour range described by programs such as New York State's storage incentives. That battery does not create 10 kilowatt-hours of energy; it simply holds up to that amount, provided your solar or grid actually delivers it. If your overnight loads draw 8 kilowatt-hours and your battery plus power electronics return about 90 percent of what they receive, your charging sources must deliver just under 9 kilowatt-hours into the system to cover that night comfortably. If clouds limit your daytime production to 6 kilowatt-hours, no chemistry on Earth will conjure the missing 3.

Under the hood, the energy lives in atomic bonding and solvation, not in some vague electron pressure. Research from chemistry educators emphasizes that the driving force in cells such as classic zinc-copper or modern lithium-ion comes from differences in how strongly metals are bonded and how stable their ions are in the electrolyte. High-energy materials like zinc or lithium are willing to move to a lower-energy configuration, and that downhill move is what pushes electrons through your devices. Rechargeable cells are engineered so that this move can be reversed with an external push, but the direction is always set by the underlying chemistry, not by magical energy gain.

All batteries store direct current (DC). Alternating current (AC) from the grid or from some generators must be converted to DC before charging. Explanations from battery manufacturers point out that AC cannot be stored directly because its constant direction reversals would cancel out charging and can damage the cell. That is why every serious off-grid or retrofit system includes inverters and rectifiers around the battery instead of connecting AC straight into it.

The Bucket Analogy in the Real World: Round-Trip Efficiency and Leaky Storage

The bucket analogy becomes very concrete when you compare different storage technologies side by side.

Storage type |

What is stored |

Typical round-trip result |

Typical role in a power system |

Pumped hydro |

Gravitational energy in elevated water |

Around three quarters of input power returned |

Large-scale grid balancing and long-duration shifting |

Lithium-ion battery |

Chemical energy in solid electrodes |

Up to roughly 90 percent returned |

Home batteries, EV packs, utility-scale battery plants |

Flow battery |

Chemical energy in liquid electrolytes |

Roughly 60 to 70 percent returned |

Long-duration, high-cycle grid applications |

Energy agencies and technical fact sheets agree on the big picture: pumped hydro still dominates global bulk storage capacity and usually returns about 70 to 80 percent of what it takes in, sometimes a touch more in optimized systems. Lithium-ion dominates battery storage because it combines high round-trip efficiency with compact size and falling costs. Flow batteries are less efficient but shine when you need very long duration and extreme cycle life.

In every case, the bucket leaks. Water rubbing through pipes and turbines wastes energy as heat in a pumped-storage plant. Internal resistance and conversion electronics waste energy in a lithium pack. Pumping electrolyte and running pumps, controls, and auxiliary systems waste energy in a flow-battery installation. Policy and research organizations routinely list round-trip efficiency as a key performance metric precisely because no technology beats basic thermodynamics.

For an off-grid homeowner or a business retrofitting backup power, this means that every kilowatt-hour you see on a meter after discharge started its life as more than one kilowatt-hour at the input. Planning that gap is the difference between a system that quietly rides through storms and one that surprises you with early cutoffs.

Why Batteries Feel Like They Create Energy in Off-Grid Systems

If batteries are just buckets, why do they sometimes feel like generators? The illusion comes from time-shifting and from wasted energy you never saw before you had storage.

Without batteries, a rooftop solar array often throws away midday production once loads and any limited grid export are saturated. National grid operators and renewable-integration studies repeatedly point out that excess solar and wind output is routinely curtailed when the system cannot absorb it. Add a battery, and those midday watts now land in your bucket instead of being spilled. When you flip a light on at midnight, that stored energy feels like extra power even though it is simply power you had been wasting earlier.

The same story plays out at grid scale. Energy analyses and case studies from California and other markets show that batteries charged when solar output is high can later replace fossil-fuel peaking plants during evening demand spikes. The result is cleaner, more flexible power, but still no free lunch: the energy originated in the sun and wind, not inside the battery containers.

For off-grid cabins, remote facilities, or homes in outage-prone regions, this time-shifting is exactly the point. Well-sized storage lets you bank daytime solar and use it overnight, ride through storms, and keep refrigeration, communications, and critical medical devices powered when the grid is down. Reports from utilities, research labs, and state programs consistently frame batteries as reliability tools that make renewable energy usable around the clock, not as independent sources that create energy out of thin air.

Practical Sizing: Getting the Bucket Right for Lithium Retrofits and Off-Grid Power

When planning a lithium retrofit or an off-grid system, the starting question is not "How many batteries can I afford?" but "How many kilowatt-hours do my loads actually consume, and how much energy can my sources reliably supply?" That pushes you into a simple but essential accounting exercise.

First, estimate daily energy use by multiplying the power of each major load by the hours you plan to run it. A 1-kilowatt well pump that runs for 1 hour uses about 1 kilowatt-hour. A 200-watt refrigerator that averages 8 hours of run time over a day uses about 1.6 kilowatt-hours. Add up lighting, electronics, tools, and any seasonal loads such as air conditioning or heat pumps. You now have a realistic daily kilowatt-hour target instead of a guess.

Next, look at your charging sources. Solar, for example, produces within a limited window and varies with weather. Energy-storage fact sheets emphasize that batteries mainly shift energy; they do not increase total production. If your array averages 8 kilowatt-hours of usable production on a winter day, you cannot design a 10 kilowatt-hour battery bank and expect it to recharge fully every night without supplemental charging. A larger bucket does not fix an undersized faucet.

Finally, fold in round-trip efficiency and battery health. Technical briefs on residential storage stress that you should not plan to drain batteries to absolute empty every day, because every chemistry has finite cycle life and deeper cycles shorten it. Lithium-ion generally tolerates deeper daily cycling and more cycles than lead-acid, but you still want a margin. If your lithium system realistically returns about 90 percent of what you feed it and you aim to use about 8 kilowatt-hours overnight, you should design your array and grid backup to deliver closer to 9 kilowatt-hours into the pack on an average day. That margin covers conversion losses, inefficiencies, and some degradation over time.

This bucket-first thinking flips the script. Instead of chasing vague backup capacity, you are matching a quantified bucket (battery) to quantified faucets (solar, grid, generator) and quantified drains (loads). That is exactly how grid planners look at storage in studies from organizations like NREL and the International Energy Agency, and it works just as well at cabin or small-business scale.

Pros and Cons of Relying on Batteries as Your Main Bucket

Treating batteries as your primary energy bucket has real strengths. Storage smooths the natural variability of solar and wind, lets you harvest energy when it is abundant or cheap, and release it when it is scarce or expensive. Policy fact sheets point out that this flexibility reduces the need for fossil backup plants, cuts emissions, and hardens the grid against extreme weather. At the site level, pairing batteries with rooftop solar or small wind can significantly reduce outage impacts and bills by covering evening peaks and demand charges.

However, the bucket comes with baggage. Battery reports and sustainability discussions highlight that these systems have finite cycle life, require careful management, and depend on mined materials such as lithium, nickel, and cobalt. While recycling and alternative chemistries such as sodium-based or iron-based batteries are advancing, they are not yet a complete antidote to supply and environmental concerns. There is also the reality of capital cost: although lithium-ion prices have fallen by more than 90 percent over the last decade in some markets and continue to drop, installing a robust storage system is still a significant investment.

Other storage options carry their own tradeoffs. Pumped hydropower and compressed air stand out for large-scale, long-duration storage but require specific terrain or geology and long permitting timelines. Flow batteries offer outstanding cycle life and easy scaling by enlarging tanks but accept lower round-trip efficiency. Thermal storage can be inexpensive and long-lived for heating and cooling but does not directly power electrical loads. The unifying theme across all of them is that they behave like specialized buckets tuned to particular jobs, not like power plants that create energy on demand.

For a homeowner or facility manager focused on lithium retrofits and off-grid optimization, the practical takeaway is simple. Batteries are powerful tools for shifting, smoothing, and stabilizing the energy you already have access to. They reward clear math, realistic expectations, and thoughtful integration with generation and efficiency measures; they punish wishful thinking that treats capacity labels as magic.

Brief FAQ: Common Misconceptions About Battery Creation of Energy

Can a battery ever give back more energy than it took in?

No. All the major storage technologies described by research labs, utilities, and energy agencies have round-trip efficiencies below 100 percent. Some, like pumped hydro and lithium-ion, get close enough that losses may not feel obvious in day-to-day use, but none create energy. Any claim that a battery or storage system delivers more energy than it receives conflicts with basic conservation laws and with the measured performance data used to design real projects.

Why does my battery bank seem to run out faster than its nameplate suggests?

Several factors combine to make usable capacity smaller than the label. Part of the stored energy is lost in conversion and internal resistance, especially at high power draws. Most systems are not operated all the way to 0 percent state of charge every cycle, because deep discharge shortens life, particularly for lead-acid chemistries. Over time, cycle aging and high temperatures permanently reduce capacity, a behavior documented by manufacturers and explained in educational material from battery companies and agencies. The result is that the practical, long-term usable capacity is always lower than the fresh, rated number.

Do more batteries replace the need for good load management and generation planning?

They help, but they do not replace fundamentals. Stacking more batteries without enough charging sources simply gives you a larger underfilled bucket. Similarly, ignoring wasteful loads or poor efficiency will drain even a generous bank faster than expected. The most resilient systems combine right-sized storage with smart load control, efficient devices, and adequate generation. Energy planners repeatedly note that storage is most effective as part of a coordinated package, not as a silver bullet.

In the end, the safest way to think about batteries is as finely engineered buckets for energy. Fill them wisely from reliable sources, expect some spillage, and they will quietly transform your off-grid or retrofit project from fragile to robust without ever pretending to create a single extra watt-hour.

References

- https://www.energy.gov/science/doe-explainsbatteries

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Energy_storage

- https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/electricity/batteries-circuits-and-transformers.php

- https://www.nyserda.ny.gov/All-Programs/Energy-Storage-Program/Energy-Storage-for-Your-Business/Types-of-Energy-Storage

- https://www.nrel.gov/news/detail/program/2024/how-nrels-research-in-battery-energy-storage-is-helping-advance-the-clean-energy-transition

- https://www.iea.org/reports/batteries-and-secure-energy-transitions

- https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jchemed.8b00479

- https://www.eesi.org/papers/view/energy-storage-2019

- https://www.irena.org/News/articles/2025/Aug/Battery-energy-storage-systems-key-to-renewable-power-supply-demand-gaps

- https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/11/the-role-of-energy-storage-technologies-in-the-energy-transition/

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.