This article explains how lithium cell grading works, how Grade A and Grade B cells differ in performance and risk, and how to choose and verify the right grade for real‑world systems.

The real difference between Grade A and Grade B lithium cells is not marketing polish; it is how closely each cell hits the factory specification for capacity, resistance, and stability over thousands of cycles, which directly drives safety, lifespan, and cost per kilowatt‑hour in your system.

Imagine you have just spent serious money on a “3,000+ cycle” lithium bank for your cabin, and two summers later your inverter is low‑voltage tripping by midnight while your friend’s setup across the valley is still going strong. Same chemistry, same size sticker, very different real‑world performance. Field reports are consistent: banks built from true Grade A cells stay balanced, run cooler, and last years longer than cheap packs built from whatever the factory swept off the floor. This guide breaks down what Grade A and Grade B actually mean at the cell level, how that plays out in off‑grid and retrofit systems, and the practical checks that separate a bargain from a booby trap.

Why Cell Grades Exist at All

Lithium cells roll off the production line with natural variation. Raw materials have impurities, coating thickness drifts, electrolyte filling is never perfectly uniform, and tiny differences show up as changes in capacity, internal resistance, self‑discharge, and size. Manufacturers respond by grading every cell against a short list of hard numbers, typically appearance, size and weight, capacity, internal resistance, self‑discharge rate, and capacity recovery after a full charge–discharge–recharge cycle, as described by engineers on DIY Solar Forum and by LDSreliance.

First‑tier factories with tight process control may see only about 2% of cells miss one of those targets, while second‑ and third‑tier plants can see 5–10% off‑spec output, according to data shared by Vatrer Power and LTC Energy. Those outliers are not automatically trash; they are simply not good enough to ship into the most demanding contracts, such as automotive. Cells that hit every specification become Grade A. Cells that are only slightly off in capacity, resistance, dimensions, or storage time are pushed down to B‑grade. Cells that fall well outside the envelope or sit aging in a warehouse until their performance slumps are treated as C‑grade or worse.

There is another wrinkle: there is no universal, cross‑manufacturer definition of Grade A or Grade B. DIY testers have pointed out that a Grade C from one manufacturer can outperform a so‑called Grade A from another. That is why serious sources such as DIY Solar Forum and Invicta Lithium emphasize the factory datasheet and test report, not the marketing label, as your real reference.

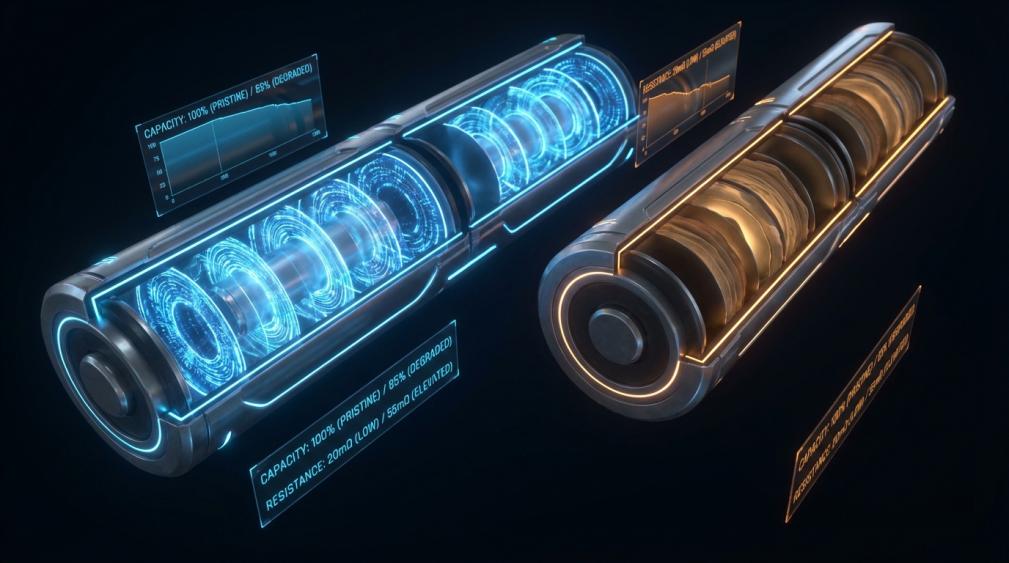

Grade A vs. Grade B: Teardown of the Specs

Strip away the stickers and you are left with numbers. When you compare cell test reports and teardown findings from sources such as UFine Battery, EVLithium, LDSreliance, ExxPower, BattSys Battery, and LTC Energy, the pattern is consistent.

Here is how the two grades differ in practice.

Attribute |

True Grade A cells |

Typical Grade B cells |

Factory spec compliance |

Meet all specifications for capacity, internal resistance, size, weight, and self‑discharge |

Miss at least one specification slightly (capacity, resistance, or dimensions) but still broadly usable |

Traceability and QR codes |

Intact factory QR codes and serials, full batch traceability and test reports |

Often scraped, covered, or missing codes; documentation patchy or absent in secondary markets |

Capacity vs. label |

Very close to nameplate, often within a few percent and sometimes slightly above it |

Slightly reduced capacity or wider spread; some cells downrated and relabeled at lower amp‑hour values |

Internal resistance and drift |

Low, tightly matched resistance and low self‑discharge; easy for the BMS to keep balanced |

Higher and less consistent resistance; higher self‑discharge, BMS works harder to keep the pack in line |

Cycle life (LiFePO₄ examples) |

Commonly thousands of cycles; many LiFePO₄ cells reach roughly 4,000–6,000 cycles |

Wide range: some honest B‑grade deep‑cycle packs are rated around 1,200 cycles; others claim more |

Price and availability |

Prioritized for EV and premium ESS use, scarce for retail buyers, highest cost |

Sold at a discount, including auction channels; often less than one‑third the cell price of Grade A |

Typical uses |

EV packs, high‑end ESS, critical medical and industrial systems |

Stationary storage, backup power, and mid‑range consumer gear where slight variation is acceptable |

Sources such as BattSys Battery and Vatrer Power note that a true Grade A lithium iron phosphate cell might even deliver a little more than its rating, for example a 100 amp‑hour cell from a top manufacturer coming in around 102 amp‑hours under standard test conditions while staying well inside all safety limits. LDSreliance and Solar‑Electric highlight that Grade A packs hold voltage, charge, and capacity almost identically from cell to cell, so the BMS can keep them in balance with very little work.

Grade B is a broad category. Some B‑grade cells are simply unsold A‑grade inventory that sat 3–6 months on a warehouse shelf and was downgraded on paper. Others missed a dimension target by a fraction of an inch or fell short by only a couple of amp‑hours on a 280 amp‑hour rating in capacity tests. Companies such as Fogstar report that their EVE B‑grade prismatic cells still use the same LiFePO₄ chemistry and are tested to around 6,000 cycles, making them suitable for motorhomes and off‑grid storage when they are transparently sold as B‑grade.

On the other end of the spectrum, LDSreliance points out that many low‑priced “Grade B” deep‑cycle batteries are actually built from mixed or lower‑grade cells and paired with marginal BMS designs, with realistic ratings around 1,200 cycles and lifespans closer to 5–10 years at light usage.

The key takeaway from this teardown is that Grade A tells you the cell met all of a specific factory’s standards. Grade B tells you it did not, or that it was stored longer, but it does not tell you how far off it is. That is why you have to combine grade with source and documentation before you trust it in a critical system.

What It Means for Off‑Grid and Retrofit Systems

When you retrofit an older RV, boat, or cabin from lead‑acid to lithium, you are not just buying amp‑hours; you are betting your lights, water, and sometimes your income on a particular stack of cells.

LDSreliance lays out a simple contrast. Grade B lithium deep‑cycle batteries can still beat good AGM lead‑acid on usable capacity and lifespan, especially in occasional‑use scenarios. A Grade B pack rated for about 1,200 cycles and used only 30 weekends per year on a fishing boat could, on paper, last decades if the BMS holds up, because you are only burning a few dozen cycles per year. In that kind of duty cycle, Grade B plus a robust BMS is often a rational budget choice.

For daily, hard cycling, the math changes. UFine Battery and EVLithium note that Grade A LiFePO₄ cells routinely deliver on the order of 4,000–6,000 cycles before you hit roughly 80% of original capacity under standard conditions. That is the difference between a bank that shrugs off more than ten years of daily cycling and one that is tired after roughly three years if you push it hard every day at a similar depth of discharge. Invicta Lithium ties this to warranty practice: batteries built from tightly matched A‑grade cells often carry 5–7 year warranties, while 2–3 year warranties tend to indicate B‑grade or poorer matching, and 1‑year warranties usually signal used or very low‑grade cells.

Solar‑Electric’s analysis of energy storage systems goes a step further. In a large battery bank, a single weak or high‑impedance cell can limit the entire string, forcing the BMS to throttle charge, cut discharge earlier, and ultimately shorten the service life of the full bank. Using Grade A, automotive‑grade cells with low, tightly matched resistance minimizes that risk. Dropping in cheaper B‑ or C‑grade cells in a full‑time off‑grid home might save some money on day one but often erodes the return on investment as capacity fades faster and maintenance headaches grow.

Fogstar, on the other hand, makes a strong case that honest, documented B‑grade cells have their place in off‑grid life. Its Grade B 280 amp‑hour prismatics, sourced directly from EVE, are marketed specifically for motorhomes, boats, golf carts, and garden rooms, with an advertised life of about 6,000 cycles. The important distinction is that these cells are clearly labeled as Grade B with full test documentation and are not repackaged as Grade A at a higher price.

For retrofit and off‑grid projects, the practical pattern looks like this: use true Grade A cells or batteries from a reputable ESS or RV brand when you power critical loads, cycle daily, or rely on the system year‑round. Use documented Grade B from transparent suppliers when the system sees moderate use, you can tolerate some variation, and budget is a real constraint. Avoid mystery‑grade or obviously mixed cells for anything that runs unattended, powers a well pump, or keeps food cold.

The Real Teardown: How to Tell What You Are Actually Getting

Marketing photos do not show grade, and labels can be misleading. A “Grade A+ premium cell” on an online marketplace might be anything from genuine EV‑grade stock to a scraped QR code reject. The only reliable way to tell is to combine paperwork, physical inspection, and basic electrical testing, as recommended by BattSys Battery, LDSreliance, UFine Battery, LTC Energy, and DIY Solar Forum.

Paperwork and QR codes

True Grade A cells leave a trail. BattSys Battery and LTC Energy both emphasize that top‑tier factories can provide original test reports listing internal resistance, open‑circuit voltage, capacity, and serial or QR codes for each individual cell. Those reports should match the codes laser‑etched or printed on the case. Solar‑Electric also stresses the importance of certifications and standardized tests such as UN38.3 and UL or IEC safety standards for serious ESS projects.

By contrast, DIY Solar Forum contributors and Fogstar both describe a common gray‑market practice: large conglomerates buy B‑grade cells, laser off or cover the QR codes, and pass them along as Grade A at higher prices. When a seller cannot or will not provide factory‑level test data and you see scraped or taped‑over codes, you should assume you are not dealing with true Grade A, no matter what the listing says.

Visual inspection and weight

Visual inspection is simple but powerful. Battery quality guides from EVLithium, UFine Battery, and EV Reporter point to obvious red flags: swelling, bulges, rust, dents, electrolyte stains, mismatched or rewrapped casings, and sloppy terminal welds. Legitimate Grade A cells should be uniform and clean, shipped in robust packaging that matches what the manufacturer uses for OEM customers, as noted by LDSreliance.

Size and weight matter too. DIY Solar Forum and Invicta Lithium both highlight that cells should fall within tight tolerances for dimensions and weight at the stated state of charge and storage temperature. A cell that is noticeably lighter than specification may be using less active material. One that is swollen at rest has almost certainly seen abuse or long‑term storage and behaves closer to C‑grade.

Simple electrical tests you can actually run

You do not need a laboratory to catch most impostors. Experienced testers on DIY Solar Forum report that capacity tests alone identify roughly 99% of bad cells.

Start by letting new cells rest at room temperature, around 77°F, then measure open‑circuit voltage. In a genuine matched batch, values should be very close to one another. A wide spread in resting voltage suggests mixed stock. Next, check DC internal resistance with a meter and compare it to the manufacturer’s specification. Grade A cells should cluster tightly, while suspect batches show wide variation and higher average resistance, as described by EV Reporter and UFine Battery.

Finally, run at least one full capacity test on a subset, ideally at a gentle 0.2–0.5C discharge rate for DIY use, or at 1C charge and 1C discharge at about 77°F if you want to match the datasheet more closely, following the method outlined by DIY Solar Forum. Grade A LiFePO₄ cells should deliver very close to their rated capacity under those conditions and recover to near 100% capacity after a full charge–discharge–recharge cycle. Testers working with 280 amp‑hour cells report that in a sample of 1,000 units, about 11% failed to hit the datasheet capacity, often short by only 2–3 amp‑hours, which still knocks them off the A‑grade list despite being usable.

Whenever test results, weight, or external condition disagree with the marketing story, believe the numbers, not the sticker.

Lifetime Cost and Risk: Why Grade A Often Wins on Value

LDSreliance notes that Grade B cells are often sold at auction for less than one‑third the price of Grade A. That price gap is exactly why many budget lithium batteries come in at less than half the cost of established brands. At first glance, that looks like easy savings.

However, when you look at cost over the life of the bank, the picture changes. UFine Battery and EVLithium report that well‑used Grade A LiFePO₄ cells often achieve thousands of cycles, commonly in the 4,000–6,000 range. LDSreliance points out that openly marketed Grade B deep‑cycle packs are typically warrantied for around 1,200 cycles, and that is when they are built with a quality BMS. Cheaper packs using lower‑quality BMSs are unlikely to achieve even that.

Imagine two 12‑volt, 100 amp‑hour batteries. The Grade A option costs more up front but delivers, conservatively, roughly three times the cycle life of a realistic Grade B alternative. Even if Grade A is almost twice the purchase price, you often end up with a lower cost per cycle and a lower chance of early replacement. Solar‑Electric’s ESS analysis reinforces that low‑grade or poorly matched cells tend to degrade faster, increasing the risk of early system failure and eroding the expected return on investment, especially in larger banks.

That does not mean Grade B is always a bad bet. Fogstar’s direct‑sourced B‑grade EVE cells show that transparent, documented Grade B can deliver thousands of cycles at a much lower purchase price when the supplier is honest about grade and backs it with test data. UFine Battery’s LiFePO₄ grading guidance emphasizes that Grades B and even C have valid roles in low‑risk, low‑duty applications. The real problem is opacity and mislabeling, not the concept of grading itself.

For long‑term off‑grid power, especially when you are cycling daily and relying on the system in all seasons, it is rarely worth designing around the weakest acceptable cell. Grade, documentation, and supplier reputation together should drive your decision, not price alone.

Choosing Your Grade for Real‑World Projects

If you are planning a full‑time off‑grid home or a critical backup bank for a business, guidance from Solar‑Electric, Invicta Lithium, UFine Battery, and LDSreliance all converges on the same point: target true Grade A cells from top‑tier manufacturers with strong documentation, proven impedance matching, and long warranties. Pay more up front to buy down risk and keep your cost per kilowatt‑hour delivered low over the life of the system.

For a weekend cabin, a fishing boat, or a van that is only used a few dozen nights per year, honestly labeled Grade B cells or batteries from a reputable supplier can make a lot of financial sense. That is especially true when the seller can show original factory test reports, clean QR codes, and realistic cycle ratings, as Fogstar does with its B‑grade prismatics.

What you should avoid, across the board, are batteries that are suspiciously cheap, vague about cell grade, short on documentation, and sold by brands that appear one season and vanish the next. LDSreliance warns that those red flags often indicate hidden compromises in both cell grade and BMS quality. When your water pump, fridge, or essential tools depend on the bank, that is not where you want to save.

Quick Answers to Common Questions

Is Grade B always risky for off‑grid use?

Not necessarily. When B‑grade cells come from a reputable manufacturer, are sold transparently as B‑grade, and are backed by real test data, they can be excellent for moderate‑duty off‑grid systems, as shown by Fogstar’s use of B‑grade prismatics in motorhomes and stationary storage. The risk comes from mystery‑grade cells and relabeled B‑ or C‑grade stock with no traceability or support.

Can you mix Grade A and Grade B cells in one bank?

Practically, you should avoid it. Invicta Lithium and Solar‑Electric both stress that pack life is defined by the weakest and highest‑impedance cells in the string. Mixing grades almost guarantees uneven aging and harder work for the BMS, which can drag down the entire bank prematurely. Keep cells in a pack as closely matched as possible in grade, model, and batch.

Why do so many products claim “Grade A” if A‑grade cells are scarce?

Because EV demand soaks up most true automotive‑grade cells, A‑grade stock is both expensive and limited for the open market. LTC Energy and BattSys Battery note that many B‑grade cells and even long‑stored inventory are rebranded as Grade A once they leave the factory. That is why original factory reports and intact QR codes matter far more than the label on an online listing.

When you treat cell grade like the foundation of your power system rather than a buzzword on a box, you design very differently. Verify, test, and choose your grade with the same discipline you bring to your array layout or inverter sizing. Do that and your power upgrade will feel less like a gamble and more like a well‑engineered win that keeps delivering year after year.

References

- https://batteryfinds.com/what-is-grade-a-lifepo4-battery-cells-how-to-distinguish-grade-a-b-and-c-cells/

- https://www.battsysbattery.com/News/How-to-distinguish-between-A-grade-B-grade-and-C-grade-18650-battery-cells.html

- https://www.safeguarduk.co.uk/caravan/leisure-battery-guide

- https://www.invictalithium.com.au/not-all-lithium-cells-are-the-same/

- https://www.evlithium.com/Blog/lifepo4-cell-grades.html

- https://evreporter.com/know-your-cell-understand-lithium-ion-cell-quality/

- https://www.grepow.com/blog/prismatic-vs-pouch-vs-cylindrical-lithium-ion-battery-cell.html

- https://www.ltc-energy.com/understanding-cell-grades-a-b-and-c-what-should-we-know/

- https://atsindustrialautomation.com/blog-posts/comparing-battery-formats-which-cell-type-is-right-for-you/

- https://www.benzoenergy.com/blog/post/the-difference-between-high-rate-batteries-cell-and-general-batteries-cell.html

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.