Manufacturing lithium batteries is typically more energy- and carbon-intensive per unit today than making lead-acid, but lead’s apparent advantage comes largely from its mature recycling loop, while modern lithium systems can deliver more useful energy over their lifetime and improve quickly as grids and recycling decarbonize.

You want to replace the heavy lead bank in your cabin, RV, or boat with a clean, compact lithium pack, but friends warn that “lithium is worse for the planet than lead.” In real off-grid upgrades where the full system is tuned around the battery, the right chemistry has cut generator runtime and fuel use enough to overshadow the factory emissions that went into the cells. This guide unpacks the environmental numbers so you can choose, with confidence, which battery bank actually shrinks your footprint over the years you plan to use it.

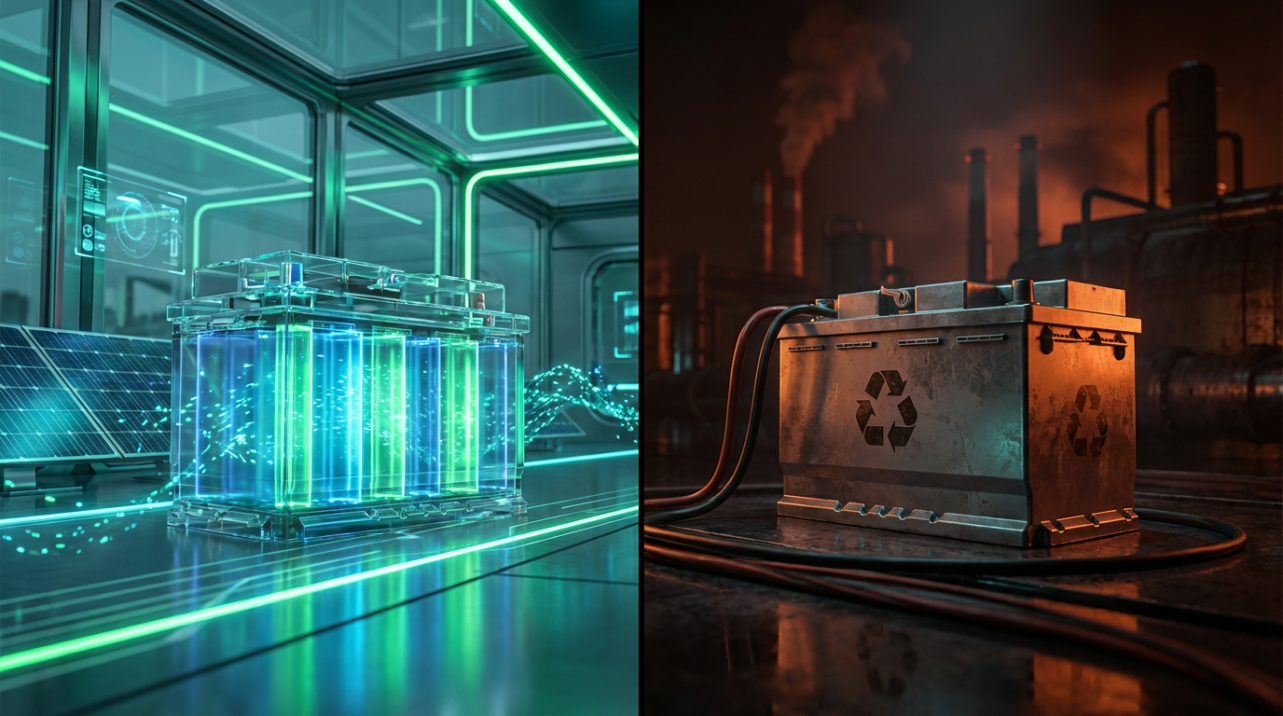

What “Dirty” Really Means for Battery Manufacturing

When people say a battery is “dirty,” they usually mix together several different issues: climate impact, water use, local pollution, human health risks, and end-of-life waste. A structured way to keep those threads straight is life cycle assessment (LCA), which tracks impacts from mining through manufacturing, transport, use, and disposal or recycling for the whole battery production chain, not just the final factory stack where cells are assembled into packs. You can see this approach in analyses of the environmental concerns of battery production chains.

For both lithium and lead-acid, the biggest environmental levers are usually the raw materials and the energy used to process them, rather than the plastic case or wiring. Mining lithium, cobalt, nickel, manganese, and lead can clear land, erode soils, and contaminate water; turning ores and brines into battery-grade materials is energy-intensive; and poor end-of-life management can leak metals and solvents into soil and groundwater. Any fair comparison between lithium and lead-acid has to look at this whole loop and ask two questions: how harmful is it to make one battery bank, and how much useful energy does it deliver before it dies.

Lithium Manufacturing: High Impacts, Rapidly Improving

Lithium-ion batteries are more material- and energy-intensive to make than the starter battery in a gas car, in part because they pack far more energy into a tighter, lighter space and rely on a complex stack of processed metals and chemicals, as highlighted in MIT’s overview of CO2 from battery manufacturing. Cathode materials must be baked at very high temperatures; aluminum-intensive pack structures add their own energy burden; and advanced cell factories run power-hungry dry rooms and coating lines.

A recent global life cycle assessment of electric-vehicle packs found that nickel-rich lithium chemistries cluster around roughly 180 lb of CO2-equivalent per kilowatt-hour of battery capacity, while lithium iron phosphate (LFP) packs come in closer to about 120 lb of CO2-equivalent per kilowatt-hour. Most of that footprint comes from the cathode materials and the electricity running through the manufacturing plants. Today, about three-quarters of the world’s lithium-ion batteries are assembled in China, where coal still dominates the grid, so the same factory running on cleaner electricity would immediately look “less dirty” in carbon terms without changing the chemistry at all.

Upstream, the mining and refining that feed lithium factories are anything but trivial. Case studies of brine extraction in South America’s Lithium Triangle and hard-rock operations in places like Western Australia show that producing one ton of lithium can demand on the order of millions of tons of water—on the scale of hundreds of millions of gallons—while some operations consume around 65% of the available water in already dry regions, as reported in reviews of the environmental impact of battery production. High-profile incidents of fish kills and contaminated rivers near lithium mines underline that in water-scarce basins, the local footprint can be severe even if the global climate math looks favorable.

Worker and community health are also real concerns. Cobalt and nickel mining and processing can release dust and fumes linked to lung disease and skin irritation, and battery factories expose workers to solvents, acids, and heavy metals that require strict engineering controls and training to avoid chronic harm, as documented in case studies of environmental and health risks in battery manufacturing. Lithium-ion cells themselves carry fire risk through thermal runaway if damaged or poorly handled, which matters both in production and during scrapping.

Recycling: Lithium’s Biggest Chance to Clean Up

Despite all the headlines about “urban mining,” only a small fraction of lithium-ion batteries are currently recycled; many estimates put global rates in the single digits, with most end-of-life cells still heading toward landfills or low-grade material recovery, making end-of-life management an urgent environmental and safety issue in assessments of lithium-ion battery recycling. Landfills see growing numbers of fires from discarded packs, and the metals embedded in those cells represent squandered energy and resources if they are not recovered.

The good news is that when lithium batteries are designed and collected for true closed-loop recycling, the climate benefits are substantial. Detailed supply-chain modeling shows that returning recovered metals directly into new cathodes can cut greenhouse-gas emissions by roughly half or more compared with using freshly mined materials, and that hydrometallurgical and direct-recycling routes dramatically reduce energy demand compared with mining. Scrapping studies find that smelting and leaching about 2.2 lb of cell material can use well under 10% of the energy and emit a fraction of the CO2 of producing an equivalent amount of material from ore, as highlighted in analyses of lithium-ion battery scrapping challenges.

Industry and policy are starting to move. Automakers and recyclers are building facilities in the United States and Europe designed to process tens of thousands of tons of lithium batteries per year, and roadmaps from the U.S. Department of Energy and the European Union envision high recovery rates and mandatory recycled content as part of a circular battery economy, themes echoed in both forward-looking recycling reviews and current industrial projects in lithium-ion battery recycling. As those systems scale and more manufacturing shifts onto cleaner grids, the “dirtiness” of lithium manufacturing should steadily fall.

Lead-Acid Manufacturing: Cleaner on Paper, Risky in the Wrong Hands

Lead-acid batteries have one enormous environmental advantage: a nearly closed-loop, highly standardized recycling system. A large life cycle assessment of auto batteries found that manufacturing lead batteries has significantly lower overall environmental impact than LFP lithium batteries, largely because spent lead units are almost completely collected and recycled into new batteries in a tight loop, as summarized in the auto-battery LCA from the Battery Council International. Lead is one of the most efficiently recycled commodity metals, and most new starter and deep-cycle lead batteries already contain a high share of recycled lead.

Design simplicity reinforces that advantage. Lead-acid batteries share similar architecture and chemistry across brands and applications: plates, separators, sulfuric acid electrolyte, and a robust case. That commonality makes it straightforward to shred, separate, and smelt materials at scale with high yields and predictable economics, so recyclers can profitably recover lead and plastic in a way that lithium plants are still working toward.

None of this removes lead’s inherent danger. Lead is a potent neurotoxin, and when recycling happens in informal or poorly regulated facilities, especially in low-income regions, emissions can poison workers and communities for generations. The relative cleanliness of lead-acid manufacturing in formal, regulated loops depends on keeping every stage—from collection to smelting—tight and well controlled. A single broken link, such as home smelting of scrap batteries, can instantly flip lead from “circular product” to “toxic legacy.”

On the user side, deep-cycle lead-acid batteries are optimized for regular discharge and recharge but are sensitive to how deeply they are cycled and how they are installed. Technical guidance on deep cycle batteries emphasizes that they should generally not be discharged below about half their capacity if you want a reasonable cycle life. Flooded, maintainable designs also vent hydrogen and oxygen gas during charging, which can corrode nearby electronics and create health and safety risks in confined cabins or vans if not ventilated properly.

So, Is Lithium Manufacturing Dirtier Than Lead-Acid?

If you only compare factory-to-gate manufacturing impacts for one battery bank, today’s lithium batteries generally carry a higher carbon and energy footprint than an equivalent lead-acid bank, especially when production is tied to coal-heavy grids and virgin metal extraction, as reflected in studies of battery manufacturing emissions. Life cycle assessments that pit lead-acid against LFP show lead-acid winning on many impact categories precisely because its materials are overwhelmingly recycled, while most LFP cells are still built from fresh lithium and phosphorus.

However, that snapshot misses the metric that actually matters in an off-grid or retrofit system: environmental impact per kilowatt-hour delivered over the entire life of the bank. LFP packs typically tolerate deeper regular discharge and more cycles than deep-cycle lead-acid, with expected lifespans of several years to well over a decade in many applications, while traditional lead banks see their life shortened sharply by deep discharges and partial-state-of-charge operation, as reflected in chemistry comparisons that highlight LiFePO4’s longer service life among common lithium types. When the system is built around daily cycling, fewer replacements and less oversizing can easily outweigh lithium’s higher manufacturing burden.

Consider a simple example. Imagine a small cabin that uses about 10 kilowatt-hours per day and needs roughly two days of autonomy for cloudy weather. A deep-cycle lead-acid bank sized for that job should only use around half of its rated capacity in daily operation to keep cycle life acceptable, so you might end up installing something like 40 kilowatt-hours of nameplate capacity and still expect to replace the bank every several years of hard service. An LFP bank sized for the same energy use can safely deliver a much higher share of its nameplate capacity each day and maintain that performance for many more years, so over a 15–20-year window you could manufacture, ship, and dispose of far fewer tons of batteries for the same delivered energy.

Lithium’s upstream mining and local water impacts are serious, but those are increasingly being addressed with better practices, cleaner process fuels, and emerging supply chains using geothermal or oil-field brines instead of the most sensitive salt flats. At the same time, studies of future lithium supply chains show that decarbonizing the electricity supply used in mining and processing, and shifting toward lower-impact feedstocks, can significantly cut total impacts, just as recycling closes the loop on critical materials.

Meanwhile, relying on a “clean” lead-acid bank that cycles hard in an off-grid system but needs frequent replacement can push you into a pattern of recurring manufacturing, shipping, and smelting, all while you burn more diesel or gas to cover inefficiencies and voltage sag as the bank ages. In that scenario, the lead-acid bank may look greener in a narrow factory LCA but lose ground in the real world when you count fuel burned and extra replacements.

Practical Guidance for Retrofit and Off-Grid Projects

For light-duty, rarely cycled backup roles—alarm systems, standby pumps, or emergency-only loads—a small sealed lead-acid battery can still be an environmentally sensible choice. The recycling chain for automotive-style batteries is well established, return points are easy to find, and a unit that spends most of its life on float charge will not see the punishing cycles that expose lead’s performance limits.

For daily-cycled off-grid cabins, RVs, vans, or boats that regularly run down and recharge their bank, a well-specified LFP pack is usually the more sustainable power upgrade over the long haul. You get higher usable capacity per pound, more years of service at the same usable capacity, and less generator runtime to top up a sagging bank, which in turn shifts emissions from frequent fuel burn to a one-time manufacturing hit. When comparing candidates, it is worth favoring cobalt-free lithium chemistries such as LiFePO4, and asking vendors whether their packs are produced on cleaner grids and under take-back programs, even if not every brand can yet quote full LCA figures.

End-of-life handling is non-negotiable for both chemistries. Research on the environmental and human health impacts of rechargeable lithium shows that spent lithium packs are metal-rich and can qualify as hazardous waste, with cobalt, copper, and nickel dominating toxicity metrics, so they should never be tossed into general trash or landfilled. Lead-acid batteries must also go through proper collection channels to keep lead out of soil and air. In practice, the simplest rule is to treat every battery as hazardous and return it to a retailer or certified recycler when it is done.

As lithium recycling scales, the gap in end-of-life performance will narrow. Scrapping analyses estimate that recycling lithium cells can reduce environmental impacts by well over half compared with mining, especially when plants are powered with renewable electricity and designed for high recovery yields, as discussed in evaluations of lithium-ion battery scrapping challenges. Pair that with second-life uses—such as reusing EV packs in stationary storage projects—and the total energy extracted from each manufactured pack can rise dramatically before those materials ever see a furnace or leaching tank.

FAQ

Does choosing lithium over lead-acid always cut my carbon footprint?

Not automatically. If you install a small lithium bank in a lightly used backup system where a lead-acid battery would have lasted a decade, the higher manufacturing emissions of lithium may not be offset in practice. Lithium starts to win when you use its strengths: daily cycling, deep discharge, and long service life that replace multiple lead banks over time while allowing you to lean harder on solar and run generators less. The more you cycle the system, and the cleaner the grid that produced the battery, the stronger lithium’s climate advantage becomes.

Is lithium iron phosphate (LFP) really better for the environment than other lithium chemistries?

In many respects, yes. Comparative LCAs show that LFP packs typically have lower greenhouse-gas intensity per kilowatt-hour of capacity than nickel- and cobalt-rich chemistries, mainly because they avoid some of the highest-impact metals and can be produced with somewhat less energy-intensive materials. Their lower energy density means you need a bit more mass for the same capacity, but in stationary and mobile off-grid applications that trade-off is usually acceptable. When you pair LFP’s cycle life and safety with recycling and clean manufacturing, it becomes one of the most promising lithium options for applications where climate and environmental performance matter as much as raw watt-hours.

What is the single most important step to make my next battery bank greener?

Beyond picking an appropriate chemistry, the biggest win is to design the whole system to minimize waste and maximize useful energy over time. That means sizing your bank and solar array so that you avoid chronic undercharging, keeping depth of discharge within the chemistry’s comfort zone, and planning for proper end-of-life return from day one. Getting those fundamentals right can easily deliver more environmental benefit than agonizing over small differences between similar batteries on a spec sheet.

The bottom line is simple: treat your battery bank as long-lived infrastructure, not a disposable accessory. When you size, install, and retire that bank intelligently, a modern lithium system will usually outperform lead-acid on real-world environmental grounds, and every upgrade you make to your power system will push both your reliability and your footprint in the right direction.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.