LiFePO4 batteries do not need hydrogen-venting systems like flooded lead-acid batteries, but they still should not be locked in a hot, airtight box; design for heat management and worst-case failure, not continuous gas production.

You might be staring at a tidy metal box or plywood cabinet, wondering if it is safe to hide your new battery bank inside and forget about it. Many off-grid and RV upgrades start exactly this way, especially after living with smelly, gassing lead-acid batteries that demanded big vent pipes and noisy fans. The good news is that you can dramatically simplify the enclosure when you move to LiFePO4. This guide explains when a “sealed box” is fine, when it is risky, and how to build a safe, code-conscious setup that works long term.

What “Breathing” and Venting Really Mean

When people ask whether a battery must “breathe,” they are really talking about two separate issues: gases and heat.

Venting in the strict sense is about moving enough air to dilute any gases the battery releases so they never reach dangerous levels during charging and discharging, especially in enclosed rooms or boxes. That is why ventilation design is treated as a safety-critical feature in traditional battery rooms and charging areas where hydrogen can accumulate near the ceiling.

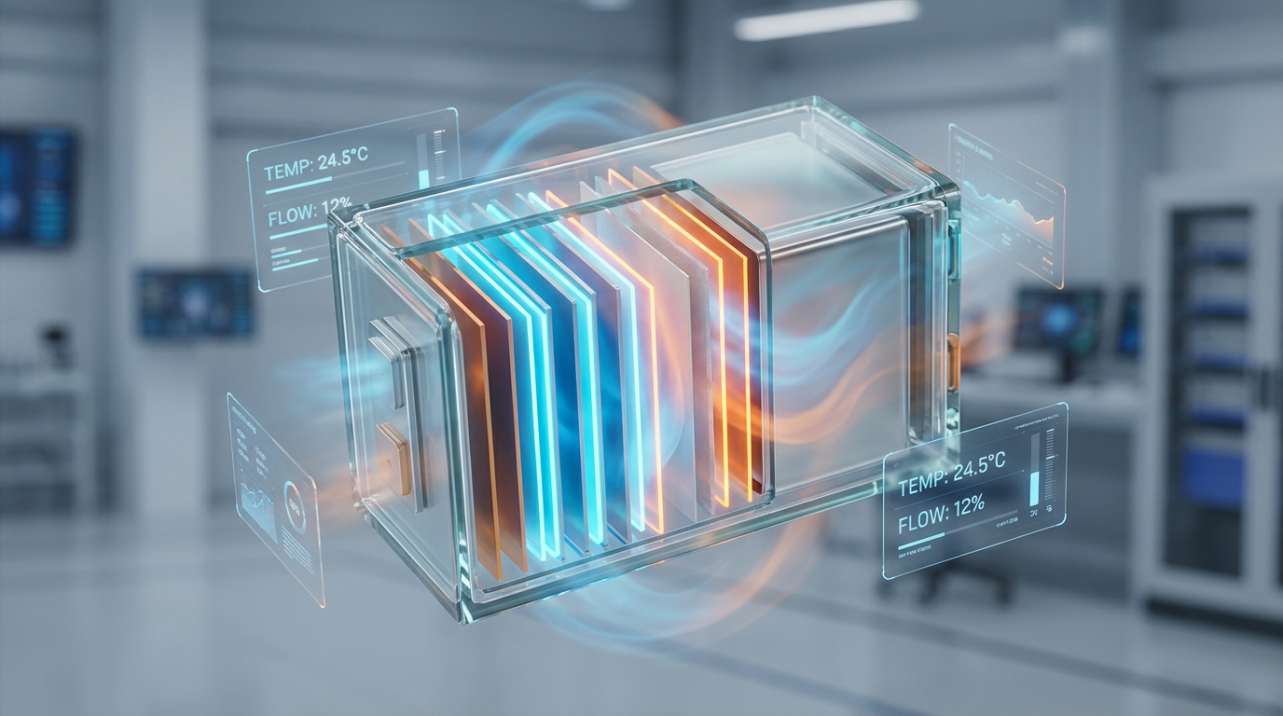

The second, quieter issue is thermal breathing. Even when no dangerous gas is produced, every battery and its electronics turn some energy into heat. If you trap that heat in a small sealed metal box, temperatures rise, parts age faster, and a very safe chemistry starts operating outside its comfort zone. Good enclosure design separates these two questions instead of blindly copying lead-acid battery room practice.

Why Lead-Acid Absolutely Must Vent

Flooded lead-acid batteries, and even many valve-regulated lead-acid designs, generate hydrogen and oxygen as they charge, especially as they move past roughly 80% state of charge and into high-rate or equalization charging. Hydrogen is extremely light and becomes flammable at around 4% by volume in air, so industrial battery room standards aim to keep concentrations well below that threshold, typically around 1%, by combining hydrogen detectors with dedicated exhaust systems that move air outdoors when gas levels rise in forklift charging rooms and similar spaces.

Safety and electrical codes for these systems were written with this behavior in mind. Guidance tied to NFPA and OSHA practice treats battery rooms as locations where hydrogen, electrolyte spray, and shock hazards are all on the table. Solutions often include gas detectors that alarm at about 1% hydrogen and trigger fans or even charger shutdowns before the room gets close to the lower flammable limit, as described in forklift battery ventilation systems that integrate detectors, ducting, and automatic fan control in one package from battery room specialists such as BHS.

Because hydrogen rises and pools at the highest points, lead-acid battery rooms often use ceiling-level vents, elevated fans, and careful duct routing to avoid dead pockets near the roof, and many engineering notes recommend assuming several full air changes per hour in worst-case designs. All of this cost and complexity exists for one reason: lead-acid batteries routinely emit flammable gas, and you must move that gas somewhere safe.

How LiFePO4 Behaves Differently

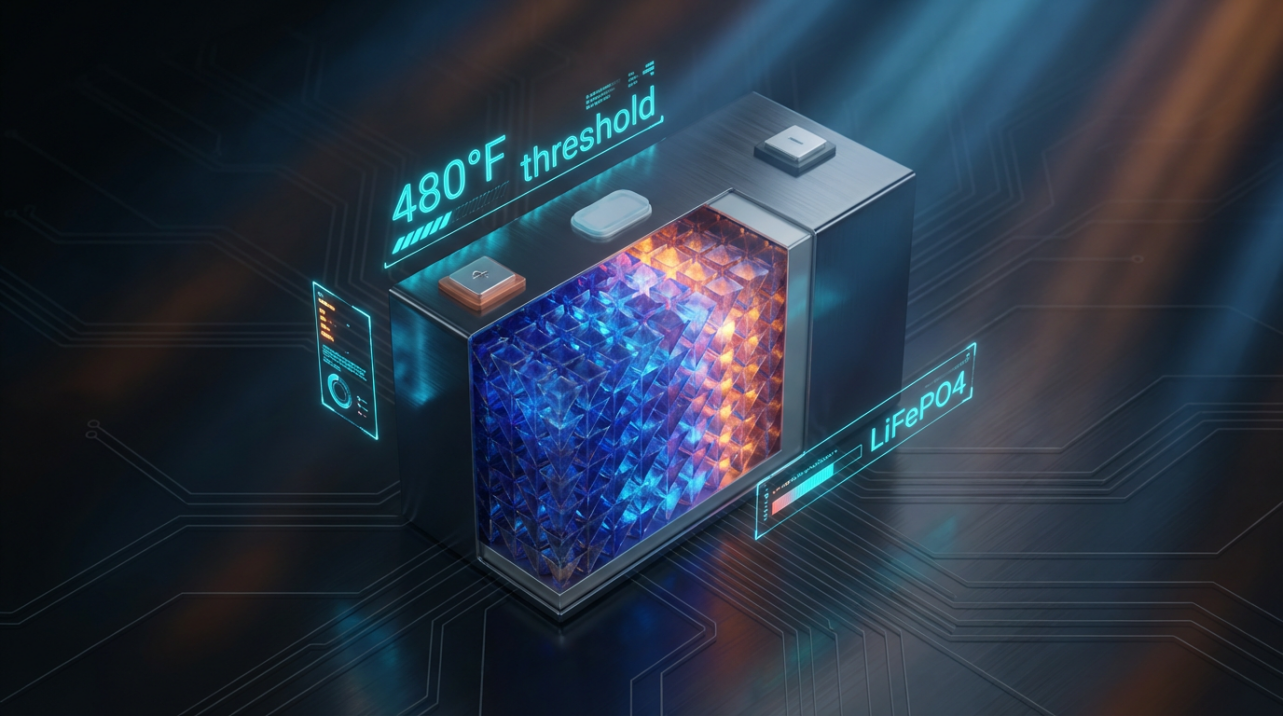

Lithium iron phosphate, or LiFePO4, is still a lithium-ion chemistry, but its iron phosphate cathode is much more thermally and chemically stable than cobalt- or nickel-based cells. Its thermal runaway threshold sits around 518°F, significantly higher than many conventional lithium chemistries, which is one reason it has become a favorite for home energy storage, marine/RV banks, and some electric vehicles, as summarized in safety-focused overviews of LiFePO4’s stability and cycle life from lithium power manufacturers such as Lanpwr.

Just as important for the ventilation question, LiFePO4 batteries produce very little gas in normal operation. Modern packs undergo minimal electrolysis during charging and discharging, so they do not steadily emit hydrogen the way flooded lead-acid batteries do. Instead, they may release only small amounts of oxygen under typical conditions rather than a flammable hydrogen-oxygen mix, as explained in LiFePO4 venting discussions from manufacturers such as Ace Battery. That is why reputable LiFePO4 suppliers state that, under normal use, these batteries do not require dedicated hydrogen-venting systems comparable to those in traditional lead-acid battery rooms.

LiFePO4 packs also ship with battery management systems (BMSs) that monitor cell voltage, current, and temperature, shutting down charging or discharging when limits are exceeded. Long-life maintenance guides stress that these batteries should still be stored and used in a cool, dry, well-ventilated area and kept within specified temperature windows during charge and discharge, even though they are far more forgiving than older chemistries in everyday use, guidance echoed in LiFePO4 maintenance recommendations from companies such as IMR Batteries and Eco Tree Lithium.

A quick comparison helps frame the enclosure decision:

Aspect |

Flooded lead-acid |

LiFePO4 |

Normal gas production |

Significant hydrogen and oxygen during charging |

Minimal gas, mainly small amounts of oxygen |

Flammability driver |

Hydrogen reaching 4% by volume |

Abnormal abuse, severe overcharge, or damage |

Code-driven venting |

Often mandatory hydrogen ventilation to stay near 1% |

Usually no dedicated hydrogen venting under normal use |

Key enclosure goal |

Prevent gas pockets and explosion |

Manage heat, protect from damage, allow safe failure modes |

The takeaway is simple: with LiFePO4 you have largely traded continuous gas hazards for thermal management and abuse resistance, without eliminating the need for basic airflow and good installation practice.

Can LiFePO4 Go in a Sealed Box?

In broad terms, yes. LiFePO4 can be installed in relatively closed boxes and compartments without the hydrogen venting hardware that lead-acid demanded. Manufacturers that specialize in LiFePO4 home and mobile packs openly state that these batteries can be used in enclosed spaces such as boats, RVs, and indoor cabinets, precisely because they emit minimal gas in normal use, a point made clearly in LiFePO4 venting explanations by suppliers such as Ace Battery.

However, “sealed” in practice should not mean “tiny, airtight oven.” Charging safety notes from LiFePO4 makers emphasize avoiding enclosed, heat-trapping spaces during charging, keeping batteries within a roughly 32–113°F operating window, and storing them at partial state of charge in cool, ventilated areas to preserve cycle life, as detailed in LiFePO4 maintenance guidelines from sources such as IMR Batteries and Lanpwr. A completely airtight metal box crammed in a hot closet above an inverter is the opposite of that advice.

For a small 12 V or 24 V LiFePO4 pack, a robust metal or plastic box with some space around the battery, cable glands for wiring, and either small passive openings or a slight gap at the lid is usually enough for thermal breathing. You do not need the kind of forced-air exhaust ducts and hydrogen alarms that industrial forklift rooms use to keep flammable gas below 1% under boost charging, as described in hydrogen ventilation system designs for lead-acid battery rooms from vendors such as BHS and Greenheck.

Indoor location still matters. Fire agencies recommend charging larger battery-powered equipment in lower-risk areas such as garages or dedicated utility spaces, keeping devices away from flammable materials and exit routes so that heat or smoke from a failure does not trap occupants. Your LiFePO4 enclosure should follow the same logic: solid walls, no clutter piled on top, and no position where a worst-case event blocks your only way out.

Example: Indoor Off-Grid Bank

Consider an off-grid homeowner, frustrated with a worn-out 12 V 100 Ah deep-cycle lead-acid battery, who plans to move to a 24 V 100 Ah LiFePO4 bank built from high-grade prismatic cells with a quality BMS for indoor use. To calm fire and fume worries, the plan stacks layers of protection: cells inside thick carbon-steel RC LiPo storage cases with non-conductive spacers, those boxes inside a metal battery cabinet, a fire blanket over the cabinet, plus sandbags and automatic fire-extinguisher balls, with gas masks ready for the family, a level of mitigation described in detail in community discussions on making indoor LiFePO4 banks safer such as those on DIY Solar Forum.

Some of that thinking is excellent. Rigid steel cases and non-conductive separators are exactly the kind of mechanical protection that prevents short circuits and physical damage, and locating the bank away from bedrooms and living areas reduces exposure if something ever does go wrong. Independent temperature sensors on the cells tied to an alarm or automatic cutoff are also a smart upgrade, reinforcing the BMS by catching an overheating cell early.

Other parts are more emotional than effective. Stacking multiple “fireproof” boxes inside one another, piling sandbags on top, and relying on extinguisher balls and gas masks does less for day-to-day safety than simply giving the enclosure a modest path for heat to escape and ensuring the room itself has good egress and a working smoke or heat detector. Fire services emphasize basics such as not charging or storing high-energy devices on combustible surfaces, keeping them away from exits, and unplugging once charged, and these principles scale cleanly from scooters and tools up to home battery banks.

A more balanced design keeps the prismatic cells in one well-built steel enclosure with internal insulation and strain relief, mounts that enclosure in a cool, accessible utility area, routes cables cleanly to the inverter, and pairs the BMS with a room-level smoke or heat detector and a modest temperature monitor.

The room, not just the box, should have enough airflow to stay close to ambient temperature during normal charging, without anything combustible stacked against the enclosure.

Practical Design Rules for Your LiFePO4 Enclosure

Start by letting the chemistry drive your decisions instead of habits left over from lead-acid days. You are no longer fighting constant hydrogen evolution, so you can drop oversized ceiling vents and big forced-exhaust systems designed around 4% flammability thresholds that dominate lead-acid battery room codes from organizations like NFPA and ASHRAE. Your design goal shifts to keeping the battery within its specified temperature range and giving it a safe way to fail without turning the surrounding space into a chimney.

Give the battery some space on all sides inside the box, and avoid foam or clothing jammed tightly around the case in the name of “insulation.” LiFePO4 guidance stresses operating between roughly −4 and 140°F, charging between about 32 and 113°F, and storing at partial state of charge in a dry, ventilated area to maximize life, as laid out in LiFePO4 charging and storage recommendations from manufacturers such as IMR Batteries and Lanpwr. A box that allows natural convection around the case, with cables that are not overstressed or bent sharply at the gland, goes a long way.

Think about failure detection rather than just containment. A simple temperature probe on or near the cells, a BMS with accessible alarms, and a smoke or heat detector in the battery room give you early warning long before anything becomes life-threatening. Fire safety agencies recommend working, interconnected alarms anywhere you charge or store significant lithium energy and urge users not to charge while asleep or in exit paths.

Finally, remember that some jurisdictions now regulate stationary energy storage systems explicitly, even when they use LiFePO4. General NFPA and workplace safety guidance treats any high-energy battery installation as an energized electrical system that deserves a documented safety plan, training, and appropriate access control. If you are doing a permitted home battery installation, the local authority may still expect a ventilation strategy for the room as a whole, even if the chemistry itself does not demand hydrogen venting.

Quick Answers to Common Questions

Is a vented lead-acid battery box overkill for LiFePO4?

In most cases it is more than you strictly need for gas management, but it is not a problem to keep the venting; you simply retire the hydrogen-driven fans and equalization settings that lead-acid required. The existing ducting can help move heat and keep the room comfortable without having to meet the 1% hydrogen design thresholds that industrial lead-acid battery rooms target, as described in forklift battery ventilation articles from companies such as BHS and Greenheck.

Do you need a hydrogen detector for a LiFePO4 bank?

For typical home and RV LiFePO4 systems the answer is no, because the batteries do not continuously emit hydrogen under normal conditions and the risk profile is very different from a flooded lead-acid room where codes and best practices call for detectors that alarm at 1–2% hydrogen by volume, as outlined in hydrogen gas detection guidance for lead-acid charging rooms from BHS. You gain far more by investing in good BMS hardware, temperature monitoring, quality cabling, and room-level smoke or heat alarms than by installing sensors designed for a gas your system barely produces.

Is it safe to sleep in the same building as an indoor LiFePO4 bank?

For well-designed systems, yes, and this is exactly the role LiFePO4 plays in many home energy storage products that pair long cycle life with enhanced thermal stability around 518°F, as described in LiFePO4 safety overviews from manufacturers such as Lanpwr. The key is not merely the chemistry but the installation: place the bank in a utility space, follow manufacturer charging and temperature limits, maintain basic room ventilation, and protect escape routes, matching the general lithium battery safety recommendations from fire services.

A LiFePO4 upgrade is one of the most powerful safety and performance improvements you can make to an off-grid or backup system, but it only delivers its full advantage when the enclosure matches the chemistry. Skip the forklift-style hydrogen gear, give your bank a cool, clean, modestly ventilated home with smart monitoring, and you will have a quiet powerhouse that works hard without demanding much “breathing room” at all.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.