Cranking an outboard with lithium is only “bad” if you treat it like a drop-in lead-acid replacement; when you design and maintain the system for lithium’s behavior, it can start cleaner, run longer, and lighten the whole boat.

You know the feeling: you twist the key at the ramp, everything on the dash goes dark, and the day you planned on chasing fish turns into a slow drift toward the dock. Many of the “lithium burned me” stories trace back to the same pattern of mismatched batteries, chargers, and wiring that ignores basic marine safety guidance. This guide shows how lithium really behaves on a starting circuit, why cautious captains are not wrong to be wary, and the choices that turn a risky retrofit into a dependable power upgrade.

The Real Reason Captains Distrust Lithium for Cranking

Most of the horror stories you hear are not about lithium chemistry itself; they are about abrupt power loss and fire risk when a high-energy battery is thrown into a system designed around the softer, slower behavior of lead-acid.

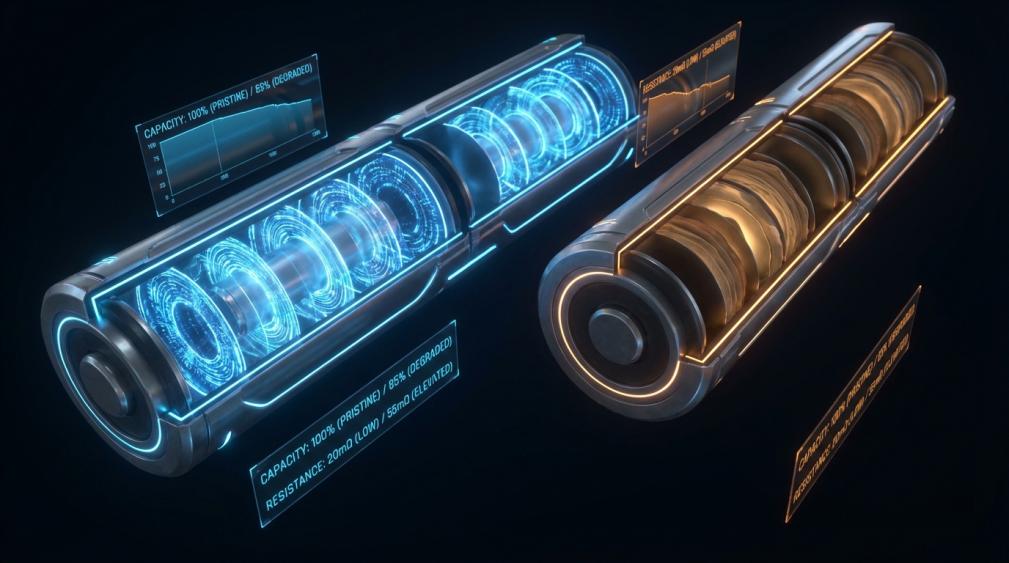

Traditional marine cranking batteries sag gracefully. As a lead-acid battery gets low, voltage droops and electronics dim, which gives a warning that it is time to shut things down and save the next start. Marine supplier guides describe this gradual decline, with a typical 12 V lead-acid resting around 12.6–12.7 V when full and falling toward about 11.8 V as it nears 20 percent state of charge. Lithium deep-cycle batteries behave differently. A LiFePO4 pack will sit around 13.3–13.4 V when full and still hold roughly 13 V even near 20 percent state of charge, then its Battery Management System cuts off to protect the cells, often in an instant rather than a slide. Lithium buying guides emphasize that you should not rely on “it feels weak” as a warning with lithium, because the power stays strong right up until shutoff.

That sharp edge is exactly what spooks captains. When the battery management electronics decide conditions are unsafe, they disconnect the bank. Battery-focused lithium standards from the American Boat and Yacht Council require that lithium batteries include integrated management systems and that the boat provide a visual or audible alarm before a shutdown so the operator can react. Those same standards recommend a separate independent power source for critical electronics so that navigation and safety gear do not die when the main lithium bank trips. On a small outboard boat, that translates to a simple reality: if you crank directly off the only lithium battery and it drops out, you lose the engine and the instruments in one shot.

There is also a deep unease around fire. High-profile marine and shoreside incidents, from yachts lost to poorly built e-toy batteries to apartment fires linked to low-grade mobility packs, have made “lithium” synonymous with “burns.” Safety analyses by marine insurers and technical magazines point out that the common triggers are overcharging, physical damage, internal or external short circuits, and charging with mismatched or overly aggressive chargers. Lithium-specific fire research for ships has shown that once thermal runaway starts, battery fires can produce jet-like flames, explosive gas mixtures, and toxic smoke that are harder to manage than conventional fuel fires. That is why multiple marine safety sources insist on using marine-rated lithium batteries, matched chargers, good ventilation, and on treating the small e-bike and gadget batteries on board as the primary fire risk rather than a properly installed LiFePO4 house bank.

Another reason for the “never crank with lithium” rule of thumb is the charging system. Installation guidance for yachts warns that lithium’s low internal resistance lets it pull very high current from a traditional alternator, which can overheat and destroy stock regulators if you just bolt a lithium pack where the old starting battery sat. Designers now call for lithium-specific charging profiles and, on many installations, dedicated DC–DC chargers or external alternator regulators to keep alternator temperature and current under control.

Put those three together—instant cutoffs, more concentrated fire risk if misused, and the chance of cooking an outboard’s charging system—and it is understandable why the conservative answer at the dock is “stick with lead-acid.” The good news is that every one of those issues can be engineered out when you design around lithium instead of pretending it is a magic lead-acid.

What Lithium Gets Right Compared with Lead-Acid

When you optimize the system, lithium brings real gains for both starting and house loads. Boat and battery manufacturers consistently highlight three advantages: lighter weight, more usable energy, and longer life.

Marine lithium iron phosphate batteries typically weigh about one-third as much as comparable lead-acid units while delivering similar or greater usable capacity. Safety and product literature for marine lithium describes roughly 70 percent weight savings and far higher energy density than traditional batteries. On a small outboard boat, dropping 60 or 80 lb from the stern by replacing multiple flooded batteries with one or two lithium packs can noticeably improve holeshot and trim.

Voltage stability is the second big win. Technical overviews explain that a 12 V LiFePO4 pack is really four cells in series at roughly 3.2 V each, so the full pack lives around 12.8–13.2 V across most of its discharge curve, whereas a lead-acid battery starts lower and sags more as it drains. One lithium buying guide gives a simple example: a small graph display drawing about 1 amp could run for days on a 50 amp-hour lithium battery, but if that same battery also feeds several graph displays, livewells, lights, and other accessories drawing 10 amps total, runtime drops to around 5 hours. The key difference is that the lithium system delivers nearly full brightness for those hours instead of fading out as voltage droops.

Longevity is the third lever. Multiple marine and off-grid sources describe lithium packs rated in the 3,000 to 6,000 full charge cycle range, and some marine insurers note that a well-maintained lithium bank may last more than ten years. By contrast, conventional marine lead-acid batteries are often worn out after a fraction of that cycling. Lithium also spends less of its life in high-heat, high-corrosion modes because it does not need constant float charging, and it eliminates the acid spills, watering, and sulfation that dominate lead-acid maintenance.

These advantages are why many boat builders and retrofitters move to a hybrid layout: lithium for house loads and sometimes cranking, lead-acid or AGM where the design or insurer demands the most conservative approach. Lithium clearly is not the villain; the system design is.

Here is a simple comparison, based on marine battery guidance and safety notes:

Aspect |

Traditional Marine Lead-Acid Cranker |

Marine LiFePO4 Used for Cranking/House |

Weight |

Heavy; more stern weight and less payload |

Roughly one-third the weight for similar energy |

Voltage behavior |

Gradual sag as it discharges, visible “weak” starts |

Holds near full voltage, then protective cutoff |

Maintenance |

Electrolyte checks, cleaning, sulfation risk |

Minimal; mainly inspections and monitoring tools |

Lifespan |

Shorter cycle life, sensitive to deep discharges |

Thousands of cycles with managed depth of discharge |

Safety profile |

Acid, corrosion, explosion risk if abused |

No acid; fire risk if misused; relies on BMS and correct charging |

When Lithium Cranking Is the Wrong Move

There are situations where cranking an outboard from lithium really is a bad idea and should be avoided.

The first red flag is using the wrong kind of lithium battery. Technical safety articles and insurer guidance emphasize that not all lithium chemistries are equal. Lithium iron phosphate is widely highlighted as more thermally stable and currently the only chemistry approved for yacht installations in some jurisdictions, while cheaper cobalt- and nickel-based chemistries used in e-bikes, scooters, and laptops are more prone to thermal runaway. Insurance and safety specialists explicitly warn against bringing high-risk e-toy packs and improvised modules on board, or using them to power critical loads. If a battery pack is not designed and certified for marine use, lacks recognized testing marks, or does not clearly state its internal management capabilities, it has no place on your starting circuit.

The second red flag is ignoring installation standards. ABYC’s E-13 lithium standard makes it clear that marine lithium batteries must be installed strictly according to the manufacturer’s instructions, must be solidly restrained against movement and vibration, and must include a proper management system and alarms. Fire safety organizations looking at lithium at sea also point out that boats face unique stresses: constant pounding can damage housings, and emergency services are far away, so a single installation mistake carries more weight than it does on land. If a system does not meet basic requirements for secure mounting, ventilation, fusing, and monitoring, adding a lithium starting battery is like putting a high-compression engine on rotten motor mounts.

The third red flag is plugging lithium into a charging system that is not ready. Lithium-focused yacht guidance notes that all charging sources, including alternators, shore chargers, solar controllers, and wind generators, must be set to proper lithium profiles. Leaving a stock outboard alternator regulator to push into a lithium battery with low internal resistance can overwork the alternator, build excessive heat, and risk failure. Charger manufacturers and off-grid battery experts echo the same point: charge stages and voltage setpoints must be programmed specifically for the battery chemistry and size, or you risk both premature battery failure and potential safety issues.

Finally, if your insurer is uncomfortable with lithium and you have not done the homework to document installation, chemistries, and safety systems, you may be taking on more financial risk than you realize. Multiple marine insurance sources now ask owners to disclose battery make, model, chemistry, voltage, installation details, and compliance with recognized standards before they extend coverage or approve upgrades involving lithium.

How to Build a Lithium Starting System That Actually Works

Done correctly, a lithium-assisted starting system can feel effortless and bulletproof. The difference is that you design deliberately instead of dropping a new chemistry into an old system.

Choose the Right Battery and Role

Start by deciding what you want lithium to do. For many outboard boats, the simplest, conservative option is to keep a traditional marine-grade starting battery dedicated to the engine and add lithium for house loads only. This directly follows the ABYC recommendation for an independent power source for critical systems in case the lithium bank shuts down, while giving you the weight and cycle-life benefits where they matter most.

If you do want lithium on the cranking circuit, choose a marine-rated LiFePO4 battery that is explicitly approved by its manufacturer for engine starting or for combined starting and deep-cycle use. Product and safety guidance repeatedly stress the importance of selecting batteries built for marine environments, with robust enclosures and internal management sized for the loads they will see. Avoid repurposed EV modules or general-purpose packs that are not tested to marine vibration and shock conditions.

Check that the battery carries appropriate third-party safety certifications and that the manufacturer publishes full details on its internal management behavior: shutdown thresholds, temperature limits, and maximum continuous and peak discharge. Lithium marine guides emphasize that exceeding maximum continuous discharge or using too much of the rated capacity shortens life and can trigger protective cutoffs, so sizing is not just about “cold cranking amps,” but about runtime and margin.

Protect the Charging System

Next, protect the outboard’s alternator and any auxiliary chargers. Yacht design articles and solar-battery manuals agree on a core principle: every charging source must be configured to the battery. For a lithium starting or hybrid battery, that means:

Configure shore chargers and built-in chargers to the correct lithium profile, matching bulk, absorb, and float voltage to the battery manual. Off-grid battery experts note that incorrect voltage setpoints are a leading cause of premature failure and voided warranties.

Use a marine-grade lithium charger or a DC–DC charger between the alternator and the lithium bank when required. Lithium-focused charging discussions highlight that lithium-specific chargers do not wait for a minimum battery voltage and can safely wake a sleeping pack, while DC–DC units cap current draw to protect alternators and regulate voltage for lithium.

Respect temperature limits. Multiple marine lithium guides state that most LiFePO4 batteries should not be charged below about 32°F and operate best in a range roughly between 32°F and the mid-90s. Some systems use built-in temperature sensors or even heating elements; others depend on the battery management system’s own temperature cutoffs. Whatever the strategy, do not defeat low-temperature charging protections.

By taking these steps, you avoid the classic lithium retrofit failure where a perfectly good alternator is cooked, or a battery is driven outside its safe envelope until the management system refuses to cooperate.

Install to ABYC E-13 Mindset

Physical installation is where many outboard retrofits fall down. Lithium installation guides emphasize several repeating themes.

Mount the battery in a cool, dry, ventilated compartment, not jammed against a hot engine block. Marine lithium installers recommend avoiding high-heat engine spaces when possible and ensuring enclosures allow air circulation so heat does not build up around the battery.

Restrain the battery mechanically with trays, brackets, or straps rated for marine use. ABYC’s lithium standard and multiple safety reviews make it clear that vibration and shock can damage cells and housings; the battery should not be able to move more than a tiny amount in any direction in rough water.

Use properly sized marine-grade cables and correct polarity. Lithium bank design articles stress that undersized or poorly crimped cables can overheat rapidly under lithium’s higher load capabilities and become an ignition source. Fuses or breakers should be close to the battery, correctly rated for the anticipated currents, and installed according to the manufacturer’s wiring diagram.

Integrate alarms and monitoring. ABYC E-13 calls for visual or audible alarms before battery management shutdown. Many modern lithium batteries provide Bluetooth or networked monitoring, and marine safety guides emphasize actually using that data: watch cell temperatures, voltages, and error flags instead of treating the battery as a black box.

Combined, these steps turn lithium from a mysterious high-tech box into a well-understood, monitored component in the boat’s electrical system.

Maintenance and Safety Habits That Keep You Starting

Even with the right hardware, your outboard is only as reliable as your habits.

Routine inspections remain essential. Marine battery maintenance guides recommend monthly checks for corrosion, cracks, bulges, and loose cable connections. Clean terminals with the appropriate cleaner or a baking-soda-and-water paste, rinse thoroughly, and apply dielectric grease or a battery protector spray to keep corrosion at bay. These same sources remind owners that even minor looseness or corrosion can create voltage drop or intermittent power that feels like “mysterious” lithium behavior but is really just bad connections.

Charge discipline matters. Across chemistries, respected off-grid and marine references warn against deep discharges and prolonged time sitting discharged. For lithium, staying within a moderate depth of discharge and recharging after each outing dramatically extends life. For lead-acid starting or backup batteries in the same boat, long-term guidance is to store them fully charged, keep them above roughly three-quarters state of charge, and either disconnect them from parasitic loads or use a compatible maintenance charger.

Storage is another critical piece. Marine lithium safety and maintenance notes recommend storing lithium batteries for the off-season in a cool, dry environment, often at a partial state of charge around the mid-range, and checking them every few months to top back to that level if needed. For lead-acid batteries, battery makers suggest cool, ventilated storage above freezing, away from direct sun, on a non-conductive surface, and emphasize that conventional flooded batteries may need electrolyte checks, while sealed AGM designs are largely maintenance free.

Finally, take fire risk seriously without being paralyzed by it. Marine fire safety reports and insurer advisories agree on the triggers to avoid: overcharging with incompatible chargers, physical damage, extreme temperatures, and water intrusion. They recommend regular inspection for swelling, hissing, heat, or unusual odors during charging, replacing any damaged batteries immediately, and considering fire-resistant storage for removable packs. For larger lithium systems, research sponsored by the Coast Guard and others concludes that rapid cooling with large volumes of water or low-expansion foam is currently the most effective way to manage lithium fires, but on a small recreational boat the primary goal is prevention, early detection, and safe evacuation if something does go wrong.

When you combine these habits with a system designed around lithium instead of bolting lithium into an old lead-acid role, the outboard simply starts, day after day, without drama.

FAQ

Is lithium iron phosphate really safer on boats than other lithium chemistries?

Marine safety articles and yacht installation guidance consistently point to lithium iron phosphate as the preferred chemistry for boat house banks and, where approved, for propulsion or hybrid systems. It is described as more thermally stable than cobalt- or nickel-heavy chemistries used in many e-bikes and laptops, and some regulators only approve LiFePO4 for yacht installations. Safety incident reports note that the most catastrophic fires at sea and on shore often involve high-energy mobility packs and low-grade devices, not professionally installed LiFePO4 banks. That does not mean LiFePO4 is risk free, but it does mean a marine-rated LiFePO4 battery installed to recognized standards is considered an acceptable risk for many cruising and fishing boats.

Do you really need ABYC E-13 compliance on a small outboard boat?

ABYC standards are voluntary, but they carry weight. Marine battery manufacturers and insurers highlight that many insurance companies reference ABYC when deciding whether to underwrite a policy, and that designing a system to meet or exceed E-13 improves onboard safety and can make coverage easier to obtain or keep. For a small outboard boat, strict line-by-line compliance may not be legally required, but using E-13 as your design checklist gives you a practical roadmap: use certified marine lithium batteries with integrated management, secure them mechanically, provide alarms and monitoring, and ensure critical systems have an independent power source in case the main lithium bank shuts down.

Should you keep a lead-acid starting battery even if you upgrade to lithium?

There is a strong argument for doing so, especially on mission-critical or heavily loaded boats. Marine authors who have examined lithium house banks frequently point out that lead-acid batteries remain cheap, proven, and sufficiently safe for simple cranking duty, and that lithium belongs where you truly need maximum stored power. ABYC’s recommendation for an independent power source for critical systems also lines up with this strategy. In practice, many reliable retrofits use a conventional starting battery for the outboard and a separate lithium bank for electronics and accessories, coupled with smart charging. That hybrid layout gives you the light weight and long life of lithium without sacrificing the conservative safety margin of a traditional starting battery.

When you align chemistry, charging, installation, and maintenance, cranking an outboard with lithium stops being a gamble and becomes a smart, high-performance upgrade that works every time you twist the key.

References

- https://www.readync.gov/plan-and-prepare/protect-your-home/lithium-ion-battery-safety

- https://battlebornbatteries.com/what-are-the-abyce-13-standards-for-lithium-on-boats/?srsltid=AfmBOooTAeBS9uVX3ZLASjFxJtzpLbY_Wm0oKmMK6ouJQ8zTW2Cslsaj

- https://www.bishopskinner.com/news/boat-safety-lithium-ion-batteries.html

- https://www.dolphin-charger.com/news/electric-boats-the-risks-and-challenges-of-lithium-batteries

- https://www.elcomotoryachts.com/maintaining-your-boats-electric-motor-7-best-practices/?srsltid=AfmBOooTli7uX_5FmRwJkq0JsrO4L8lvdcVhbF1Ax7ugS6tkCtXX5JNI

- https://www.lithiumsafe.com/battery-fire-safety-marine/

- https://www.marinelink.com/news/uscg-research-center-warns-lithiumion-531019

- https://www.trexlers.com/blog/boat-battery-maintenance-tips?Tag=Boat%20Maintenance%20Tips

- https://unboundsolar.com/blog/battery-maintenance-tips#:~:text=Add%20distilled%20water%20every%202,should%20only%20use%20distilled%20water.

- https://www.wired2fish.com/electronic-tips/everything-anglers-should-know-about-lithium-marine-batteries

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.